Carlos Clavijo: “The son of the vine”

Today we are going to talk about the book by CARLOS CLAVIJO, entitled “The son of the vine”, published by Planeta in 2010. It tells the story of the adventure of a family winery that, after various misfortunes, achieves the fortune of an award-winning international recognition. Whoever does not venture will never be fortunate.

Do not be discouraged by the sentence on the cover that says “The most beautiful story ever told about the land of wine”. Although such a claim does not bode well, you will have a good time reading it, and you will also learn interesting things about the history of our wine, which is no mean feat.

The starting point is the year 1863, the year in which Rioja wine took off, due to the arrival of the oidium and especially phylloxera in France and the subsequent need to supply the French market. From this point onwards, the author interweaves the story with the everyday life of a winery in a very nice way. We witness the loss of the colonial empire, previous wars that emptied villages and vineyards, from which the young men who could not afford the exemption from military service fled. We witness caciquismo [1] in its crude local form. We witness the disaffection with the monarchy and the winds from the east that brought revolt in 1933. We witness the civil war and its odious chance of assigning sides to the good people – who walk in a Machadian manner, unconcerned with anything but their own walk, and who “where there is wine, they drink wine; where this is none, fresh water” [2]-; we witness also the post-war period with its physical and mental closure; the second world war in which wine also played the role of spy; the recreation of Europe and its market…

The geographical setting in which the winery and vineyards are located is that part of the Rioja region, known as the Sonsierra, on the banks of the river Ebro, where the villages of Alava and La Rioja coexist. The village is called San Esteban. From its description, one could have taken it to be San Vicente, until the latter is thrown into disarray by appearing in the story. The action is naturally slow, as befits the means of transport. This explains why Rivas de Tereso, which today is almost seamlessly linked to San Vicente (or San Esteban), was at that time a place of exile for presumably ungrateful settlers of the latter. Or that reaching nearby Briones in a cart pulled by oxen could turn the freshly harvested grapes sour.

The link between the region and the port of Bilbao in the mid 1850’s thanks to the railway was crucial for the marketing and take-off of fine Rioja wine. (It is still bearing fruit today, as the Rioja Academy of Gastronomy recognised by awarding one of its first prizes to the Haro Barrio de la Estación [3] Winery Association).

[1] The rule of local chiefs or bosses (caciques)leading to abusive political bossism.

[2] Famous line from the poem Soledades II by the Spanish poet Antonio Machado who ranks among Spain’s greatest 20th-century poets.

[3] Haro’s railway station district.

The book talks a lot about wine and gives us plenty to talk about. There is no aspect that does not merit a word, from the soil and its faint white stains revealing possible saltpetre, to the counterfeits that are perpetrated on it. Particularly interesting are the paragraphs sprinkled throughout the narrative that give an account of the care of the vineyard; he spares no labour or advice, including the modern bio-dynamic ones – such as the famous burying of a bull’s horn filled with manure. The advice to the woman not to go to the grape harvest if she has her period, as the grapes could turn sour, seems to underestimate its reasonable scientific value.

Two issues in particular have marked the history of Rioja wine, and are the subject of many pages. The first is its ‘madeirisation’ [1]: “To make good wine you need good grapes and good wood”. “Money can be saved on everything except these”. Indeed, the wood, or rather a specific barrel, soon became an element of typification of Rioja wine. It is no coincidence that the book begins precisely with the rescue of the protagonist in the shipwreck –“on 9 October 1895, four miles from Veracruz” – of a cargo ship that was transporting those very barrels, thanks precisely to floating in one of them. It also tells us of our protagonist’s determination to obtain good quality oak at a good price, embarking, overland, by railway from Paris to a Bosnia permanently bleeding to death, in a non-fictional adventure that would have merited the black and white colours of an epic film by John Ford. It was the 1930s and Europe was licking its wounds from the recent Great War, nursing grudges about to explode in the next one. There is no doubt that the ‘cask’ has played a major role in the development of Rioja wine, but it is worth asking today whether it has not generated tiredness and sterilising typification.

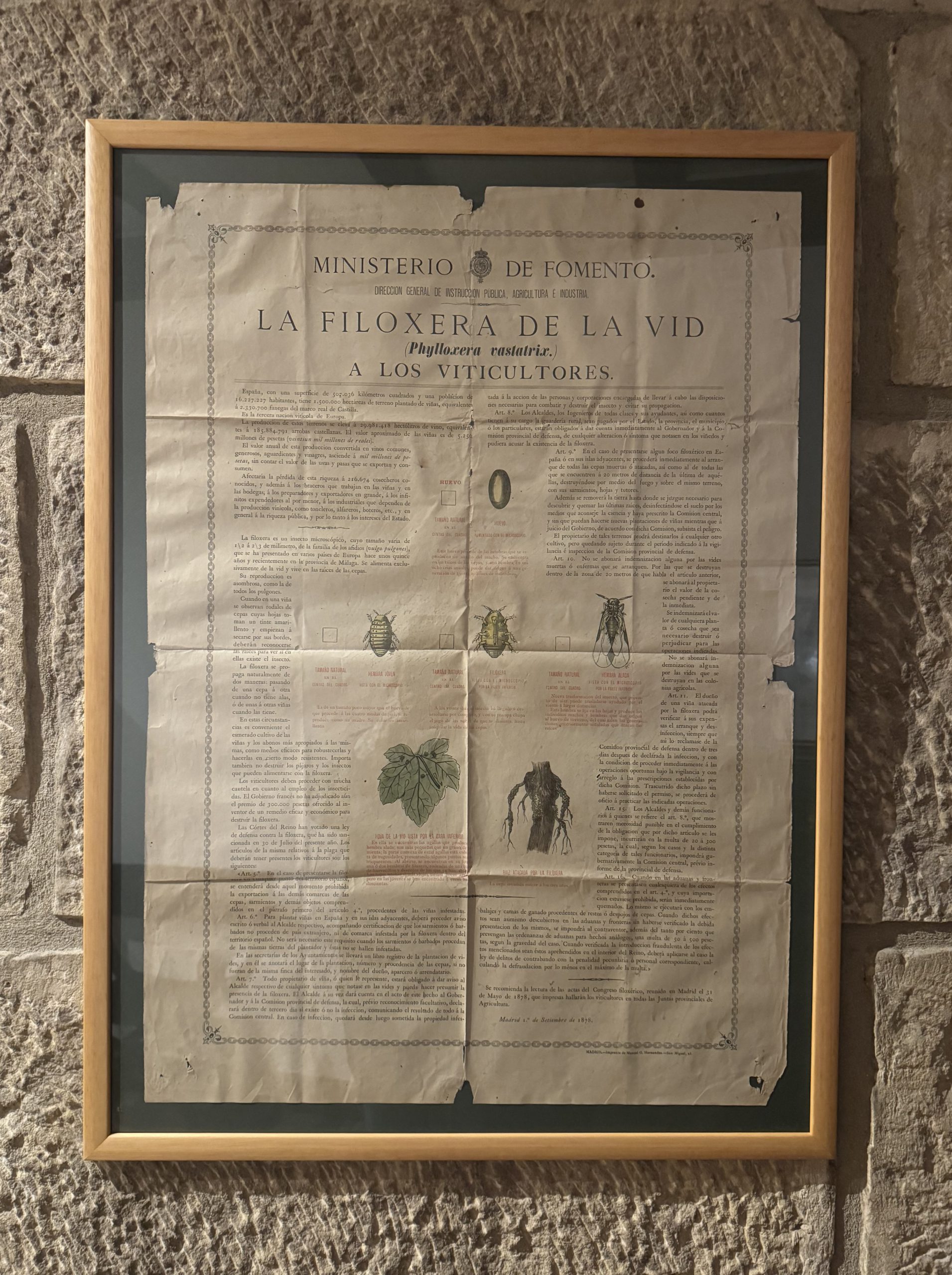

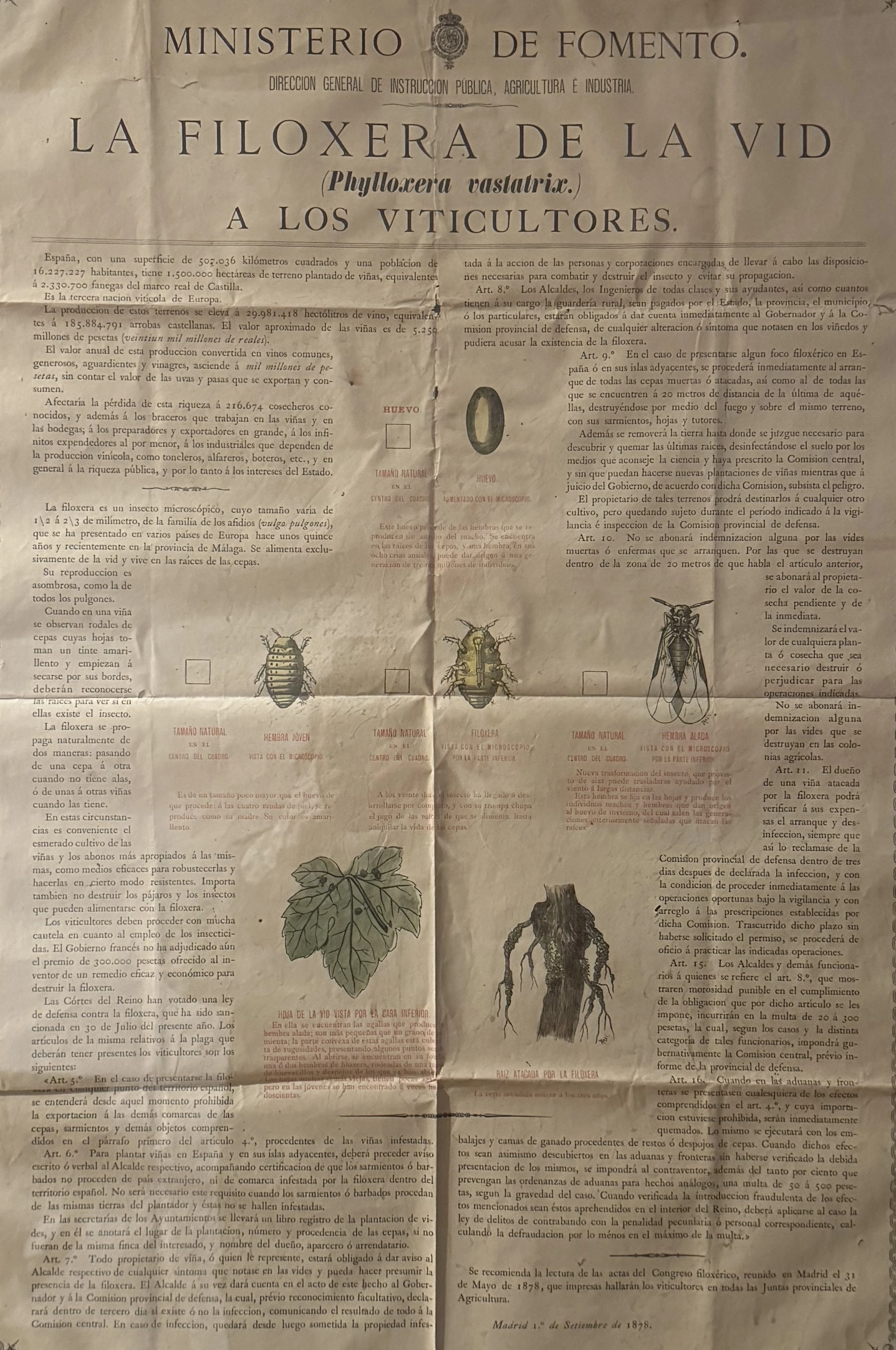

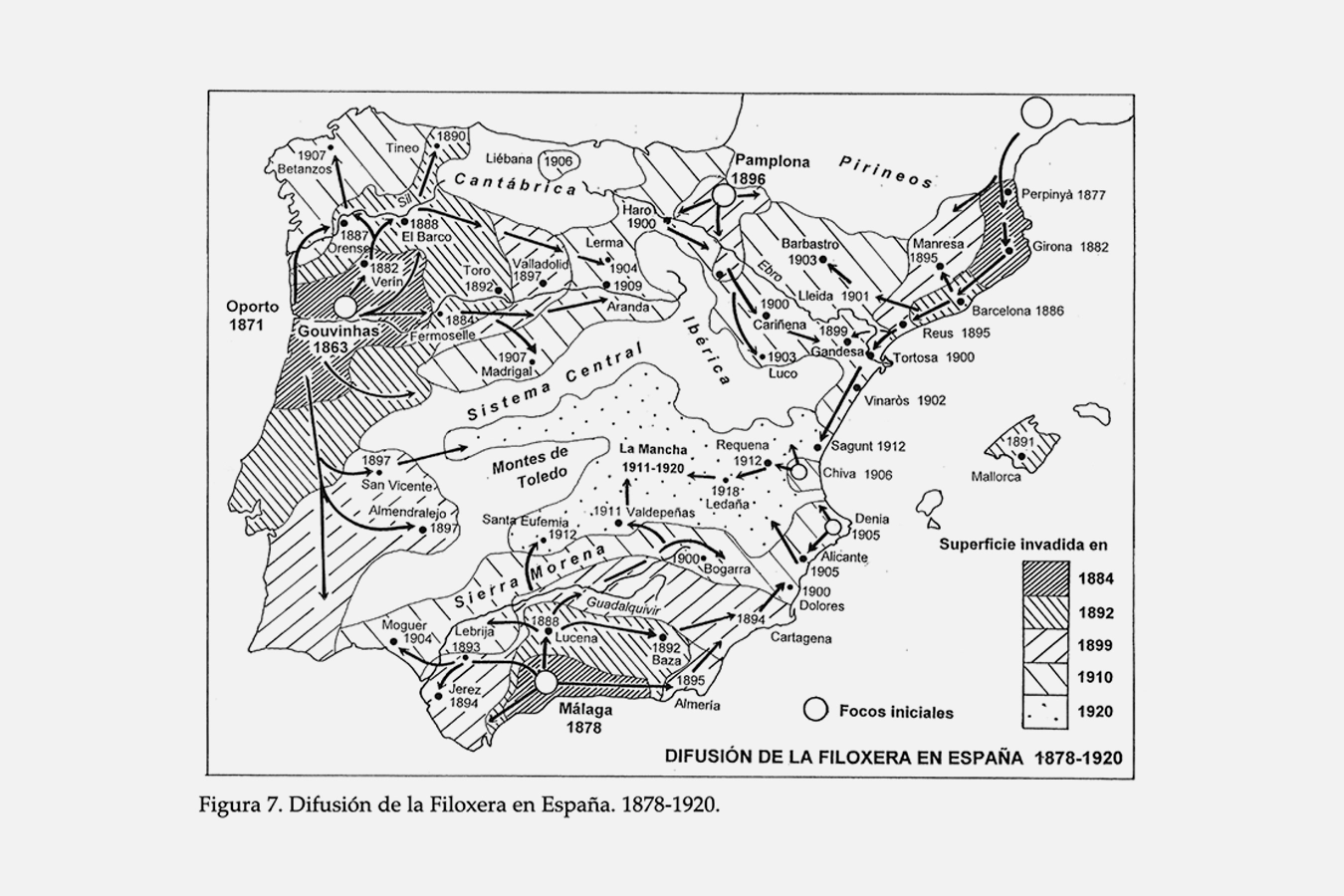

The second issue that has decisively marked the history of the Rioja is actually a very small one: phylloxera.

[1] Wine character typical for the Portuguese Madeira, which is created by the deliberate oxidative ageing and the heating or warming of the wine.

The phylloxera is an insect belonging to the order of the Hemiptera, whose existence goes through up to 18 different stages, living both above and below ground. In the former, it reproduces sexually by laying its eggs in the leaves; in the latter, when it settles parasitically in the roots, sucking the sap with its beak, it does so by parthenogenesis, i.e. without any need for stimulating males. The plant, as a means of self-protection, generates knotholes and tuberosities in the plant, which open the door to infection and eventually rot the host.

It was in 1863 when the plague arrived in France from the American continent. The period of bonanza for Spanish wine ended with the arrival of the insect in Spain; our protagonist detects it precisely on 12 July 1901. After the recent pandemic we have experienced, it is not so amazing that the invasion and spread of the disease came as such a surprise. Winegrowers had to face moments of absolute bewilderment, in which methods as esoteric as irrigation with human urine were considered; there were also witch hunts, traps and hoarding of plants, collective use of machinery…

In the end, no solution was found other than the use of American vines, planted as rootstocks, onto which the native vines were grafted, already on their aerial part. On this continent, the insect had ceased to be lethal after millions of years of parasitic coexistence, which taught the vines to defend themselves without having to immolate themselves, by producing a special sap which, by clogging the phylloxera’s chewing apparatus, prevented it from biting again.

As with any ‘scientific’ solution, this can lead to unforeseen evils if circumstances change; the claim of productivity has generalised the use of very specific genetic types of grafts and rootstocks, with a serious loss of vineyard diversity. But this is another story.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!