WINE AND LETTERS (II).- Ferrán Centelles Which wine with this duck?

I.- Ferran Centelles, who worked at the legendary El Bulli restaurant between 1999 and 2011, won the 2006 Ruinart prize for the best sommelier in Spain and was awarded the National Gastronomy Prize in 2011, among other merits, has written a book for his fellow sommeliers. Those of us who are certainly not experts on the subject should be pleased about it. We can hope that some of his teachings will be absorbed by the recipients, and therefore have a beneficial influence on us when we go to enjoy ourselves in their restaurants.

Because at the end of it all, after all the studies, tests, analyses, intuitions and conclusions about which wine, in perfect synergy with the food served, is the one that, theoretically and empirically speaking, will provide, objectively speaking, the greatest pleasure, the sommelier must go one step further. He must capture the exterior atmosphere and the inner messages of the customer, in order to obtain the same result, although now subjectively speaking, that is, he must be able to sense which of the possible wines that his knowledge dictates to him, will provide the greatest satisfaction to the consumer at that specific moment. Of course, if in order to do so it is necessary to know a lot about the psychology of customers, it is infinitely more necessary to know about wines.

The title of the book, already indicated, is “Which wine with this duck?” (¿Qué vino con este pato?), an approach to the essence of pairings. Here the duck lends itself to a play on Spanish words: obviously we are thinking of “dish” (plato). Perhaps the author is referring to different categories of ducks, for it is precisely one of them, the “Apicius duck”, which, when served with Banyuls wine, is the beginning of the modern theory of pairing, the pairing of contrasts. If the author had preferred a historical perspective, he would probably have resorted to the “eel” (anguila), for which he gives one of the earliest written references to pairing: the Romans were particularly fond of it with a good Phalernum from the region of Naples. But with eel it is more difficult to achieve synergy and perhaps even rhyme.

II.- Inevitably, at the beginning of the book, the author is busy trying to give a name to the object of the book. Pairing (in Spanish: maridaje). It seems that nobody likes the word “maridaje”, but it also seems that everybody, including the author and the author of these lines, have resigned themselves to the fact that they cannot find a better word. Harmonisation, concord, association… sound good, but they do not fit the purpose at all. Spanish words ending in “aje” that are expressive of an action sound forced, and furthermore, in the case of “maridaje”, this seems to contain an annoying gender perspective [1] that could not be further from reality, since its essence is not the assimilation of the couple to one of the factors, but the sublimation of both. That the union of drink and food is better than the sum of both elements separately. I will stick with the second definition of pairing given by the DRAE (Royal Spanish Academy Dictionary): “Union, analogy or conformity with which some things are linked or correspond to each other; e.g., the union of the vine and the elm tree, the good correspondence of two or more colours, etc.”. Can there be any more seductive pairing than this symbiosis between the vine and the elm?

The aim of “pairing” is therefore to improve the result by the sum of factors. It follows, as the author will gradually discover, that the versatility of wine is its most precious virtue when it comes to pairing.

[1] Maridaje is derived from marido. In Spanish marido means husband.

III.- In a certain way, the book traces the history of the evolution of the technique of food and wine pairing from the moment when the inadequacy of the commonplaces about it inherited from the past was perceived.

However, it should not be said that these inherited basic criteria, handed down in the domestic sphere from father to son, have lost their meaning. At least they remain for us laymen as general guiding principles. It is not unreasonable to respect that whites go better with fish and reds with meat, or sweets with dessert – except for that cloying foie gras with Sauternes, nowadays in general decline -, or that the order should be from lesser to greater in terms of colour, temperature or alcoholic strength. Factors that facilitate the choice also remain valid. For example, the adaptation to regional wines, once almost inevitable, is now more voluntary. And above all, the subjectivity of taste; there are colours to suit every taste, and wines too; we can make little mistake by firmly following this principle.

Of course, such simple pairings cannot satisfy wine experts, and even less so if one considers the evolution that food, especially restaurant food, has undergone in the last few years.

IV.- Ferrán Centelles then reviews the people who have had or are having most relevance in the evolution of the theory and practice of food and wine pairing. Most of them have published some kind of work, which is included in the very interesting bibliography that the book contains.

Each milestone in that evolution is a story. A story of people, conversations and journeys, which make the book a pleasure to read, and to follow. I take the liberty of making an organic and light-hearted classification.

Thus, he deals in the first place with:

- the “imagined” pairings with Rafa Peña and Mireia Navarro (Gresca restaurant),

- Tim Hanni’s “food pairing for the ‘diner’ and not for the ‘dinner’“,

- the “family pairing” with Evan and Joyce Goldstein;

Then with:

- the “methodological pairing” based on the elements of “contraposition and conformity” of wine and food, by Gino Veronelli and Pietro Mercadini, culminating in “Il Vino”, Enrico Bernardo’s restaurant where, in his most audacious proposal, it is the wine, the only object of choice on the part of the diner, that decides his meal.

- The “unfathomable pairing” of El Bully’s forty dishes, a challenge for which our author, who was largely responsible, managed to achieve oriental calmness through Jeannie Cho Lee, who provided the panacea of “versatility”, and to find inner peace through Jancis Robinson (“The obsession with achieving the perfect pairing sometimes creates too much pressure”) and her husband Nick Lander (“The fewer rules, the better, don’t be intimidated by the pairing”).

However, he continues his research with,

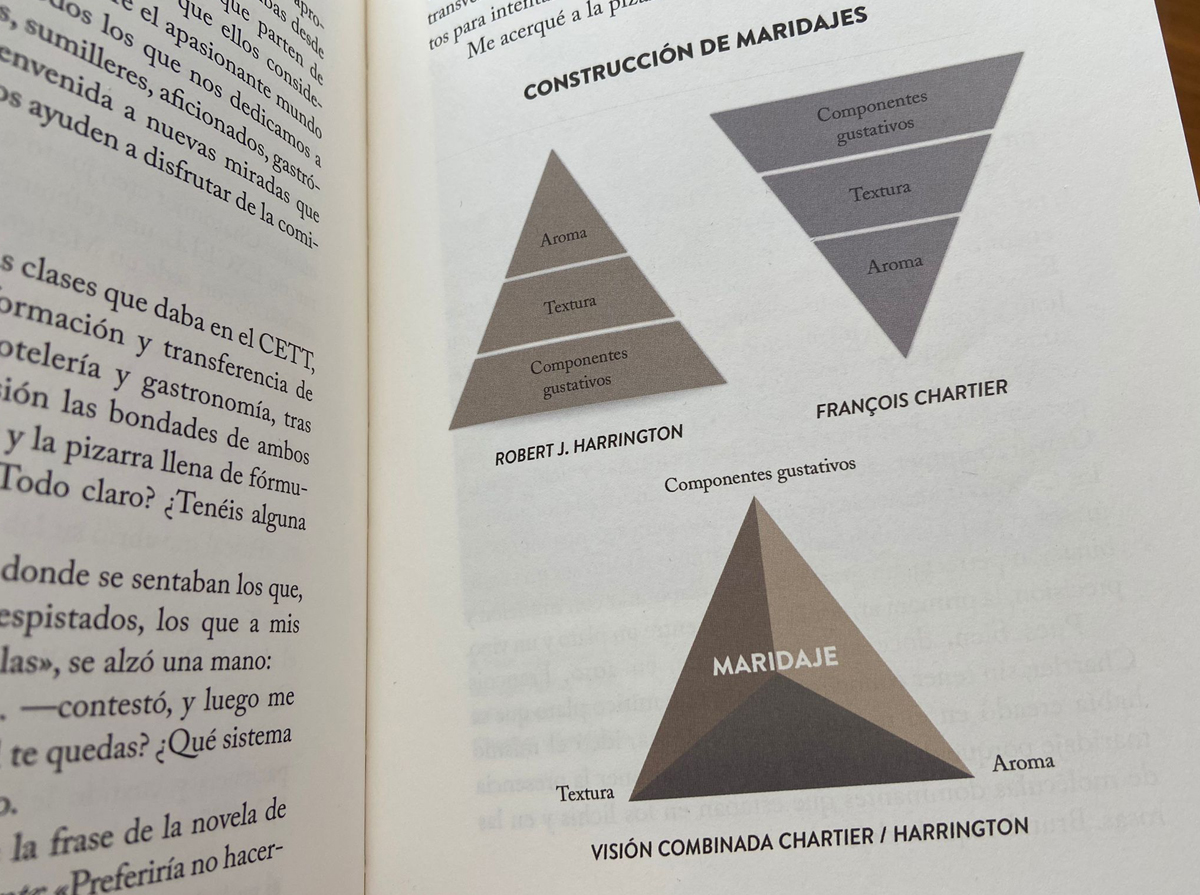

- Robert J. Harrington’s “pyramid pairing”, who places the basic tastes – salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and “umami” (“savoury”, the basic taste in Japan, today, by extension of sushi and derivatives, of universal rank, the result of monosodium glutamate) – at the base of a pyramid for the coordination of the elements, “texture” – the fat structure – at the middle level, and “aromas” at the top.

- Pierre Chartier’s “molecular pairing”, which could be described as an “inverted hierarchy” because at the base of his pyramid are the “aromas”, determined by the “dominant molecule”.

- the “cross-cutting”, synthesis or “combined” pairing about which our master author does pronounce himself: “in the pyramid, all the elements are of equal importance”.

to finish with,

- – the “integral pairing” or “relativity of pairing” of Josep Roca (El Celler de Can Roca restaurant), no pairing is suitable if it does not connect with the customer, so it is necessary to know all the rules and regulations on pairing in order to be able to break them with full knowledge of the facts for the greater satisfaction of the diner.

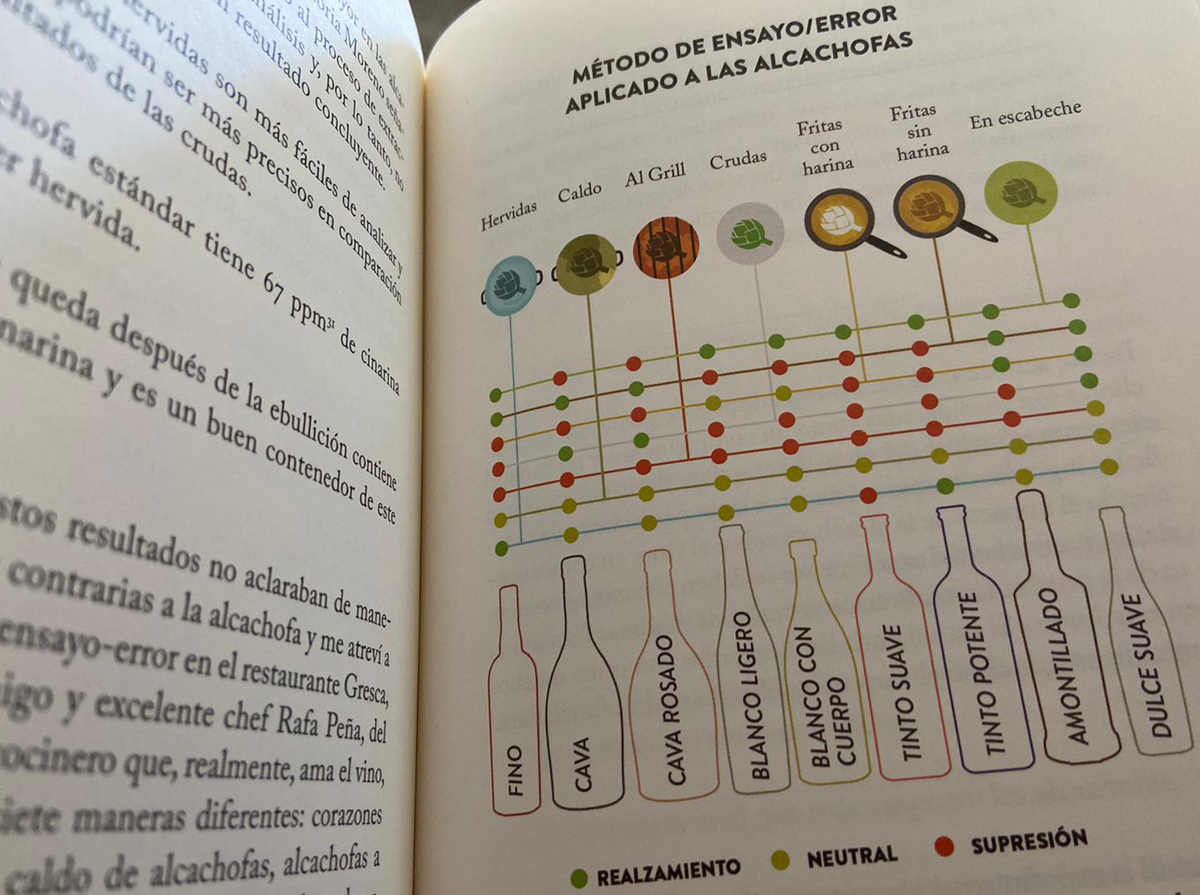

IV.- And what happens then, once all the possibilities have been analysed, with the artichokes that we all know are “inmaridables”, that is, impossible to pair? “The artichoke on the defendants’ bench” is the title of the chapter that deals with it. (Also sitting on the bench are vinegar, asparagus, eggs and chocolate – the latter to my surprise; we are back to tastes and colours: in my view, a very dark black chocolate with a powerful purplish red wine is to die for. However, a product that I learnt about thirty years ago in the kitchen of one of the most prestigious wineries in the land of the Rioja is not seated on that bench. The sign hung on the wall read: “Warning: Do not serve wine with leeks, especially if you are an expert”. I don’t know whether the sign or the kitchen, I mean, are still there, but the winery is still going strong; thus, the saying should be applied).

Allied with his friend, the aforementioned Rafael Peña, who prepared artichokes in seven different ways (raw, boiled, grilled, battered, fried, pickled, in broth), he paired them with nine Spanish wines of different profiles (cava, rosé cava, light and full-bodied whites, medium-bodied rosé, powerful red, oxidative, amontillado, txakoli). Sixty-three possible combinations to get rid of the undeserved bad reputation. Surely you will find at least one that fills you with good sensations. Preferably avoid red.

V.- By way of conclusions.

If it is a pairing in a restaurant, trust that the sommelier has read Ferran Centelles’ book to the best of his ability.

When it comes to home-cooked meals, follow his advice. And… rehearse, rehearse, rehearse… in other words, enjoy, enjoy, enjoy. And if it happens that a wine does not work with the food, you know that mistakes teach you more than successes and that nothing tragic is bound to happen, as Jancis Robinson herself says: “It’s amazing how something as absorbent and neutral as bread can act as a neutraliser”.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!