On the trail of vineyards (III): PALACIOS LOWENSTEIN

We continue our journey on the trail of vineyards, “Tras las viñas”, the book by Josep Roca and Inma Puig. Two new chapters for three great oenologists and winegrowers -how scarce and imprecise the Spanish language is to define their work-. The former is very close to our hearts. As always, what we are able to describe here is a small and pale expression of what the book has to offer.

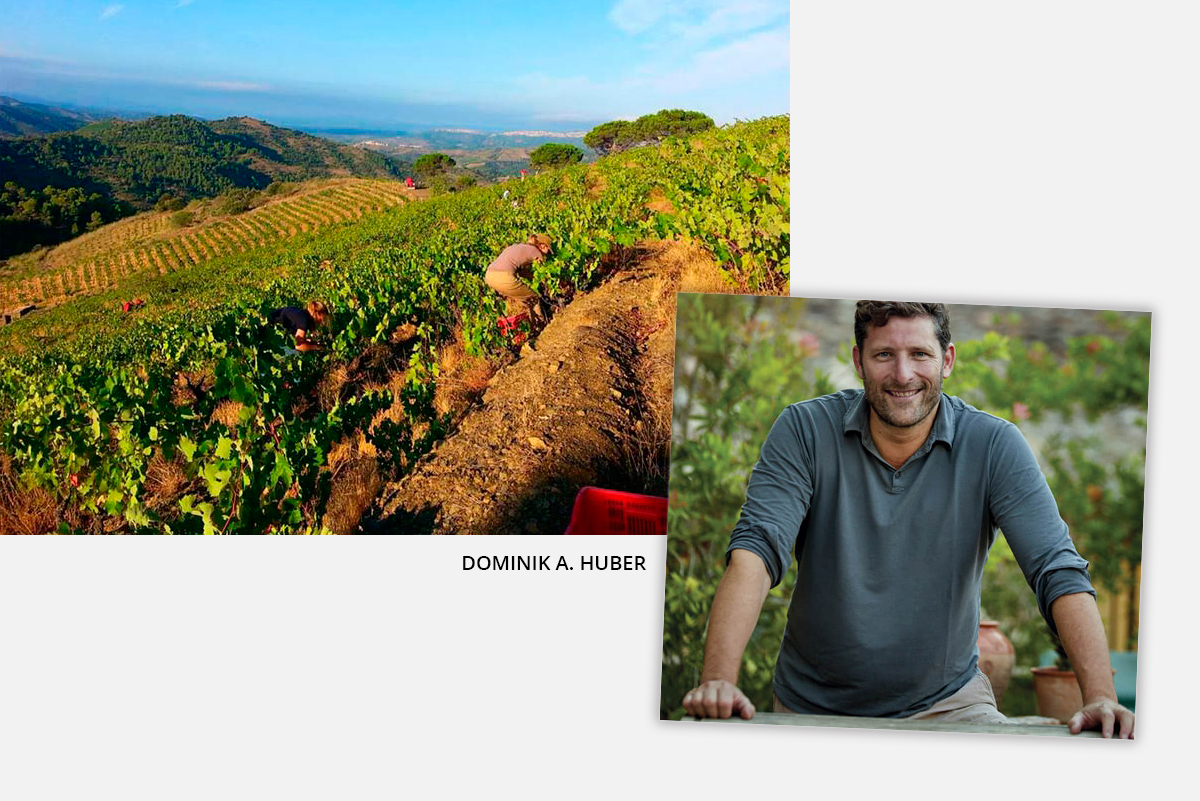

ÁLVARO PALACIOS & RICARDO PÉREZ PALACIOS Álvaro Palacios winery (Priorat), descendants of J. Palacios (Bierzo), Palacios Remondo winery (La Rioja). Spain. “The mystery of wine”.

This time there are two regions of Spain being visited: Priorat and Bierzo.

There is also mention of a winery in the land of Rioja, but there is no visit to the vineyards here, so the reference to this region will have to remain in these letters for later.

As for Priorat, I cannot help but start recalling my own memories. Way back in the early eighties of the last century, I must have travelled to Falset every week for a few months, for work reasons far removed from the world of wine (which must have had a reasonable impact on my eyes). I used to go through the interior from Tarragona via Reus.

It was a myriad of curves, of hills that followed one another as far as the eye could see, whose hidden beauty could be guessed, intuited, but I never had the time to linger on it. Many years later, but years before Laventura even existed as a possibility, I went to meet Bryan MacRobert there; it must have been in 2010 or 2011. And there I met him in a village winery in the village. It was “Terroir al limit”, a name that puzzled me at the time. The first time I saw him, he was pumping up the must in a tank, portable but large, low and wide, with his hands and arms reaching well above his elbows into the must, embracing it and stirring it at the same time.

They had prepared (he and my daughter, the cause of all the ensuing commotion) an outing, so off we went in an all-terrain vehicle, up and down hills, along paths on the verge of extinction, endless twists and turns, until we reached the top of a vineyard that gave me a complex feeling of compassion and admiration. It is called Les Tesses. There they had prepared a snack for us while we watched the sun go down. There I grasped all the beauty and mystery of the Priorat.

I was thinking about all this while reading the words of Álvaro Palacios, his search for a fragmented territory with a multitude of plots of old vines of monastic origin, the importance of geology and geo-climatic conditions, the “here ends the good and there begins the less good”, the names of the vineyards: Dofí, Les Terrasses, L’Ermita; the affinity of the plants with the environment, the magical mystery of this special wine…

And he tells us more things the story of which I try to apply to myself: the predilection for Garnacha, with a touch of Carignan, the goblet-trained vines that protect the clusters, the ecological care, the expensive wine, because without money there is no great wine, the paradoxical difficulties of the famous Rioja to sell expensive wine…

But it is not true that the best wine is made by nature. The best of all possible natures without the care of man does not produce even the worst of wines. Nature provides the sustenance, man provides the responsibility, the duty to perceive, respect and bring out all the greatness found in it.

Ricardo Palacios, Álvaro’s nephew, takes us on a visit to Bierzo. Here, we are told, buying a vineyard means buying both a mosaic of cultivated vegetation and a part of the forest; it means respecting an ancestral reality. The land and the cultivation are organised according to the characteristics of the soil, and governed by “permaculture”, which organises the vineyards according to the use of the crops and the proximity of the house. The vineyards are dry-farmed and not close to the house because it is not a garden product for daily consumption.

Varieties, mainly mencía, but also other minority varieties with some particularly suggestive names: alicante bouschet, panicarne, estaladiña, caiño, negreda, and even some old tempranillo among the reds; palomino, valenciana and godello among the whites.

Evidently, when it comes to the care of his vineyards: Las Lamas, Moncerbal, La Faraona… – the latter is named after the traditional Rioja name of the vat in the winery that contained the best wine – Ricardo honours his family lineage.

“The vineyard, the variety, the vintage and the hand of man”. That is the order of factors in the making of a good wine.

REINHARD LÖWENSTEIN Winery Heymann-Löwenstein, Winningen, Moselle. Germany. “The wines of heaven”.

Winningen is located in the area known as the Lower Moselle, in the last meanders of the river before it reaches Koblenz and therefore its final tributary destination which is to enlarge the Rhine.

It is an area of slate, scarce sunshine and humidity in which practically only white grapes thrive, particularly Riesling, which produces the most famous white wines in the world – one of my great weaknesses, less practised than it should be. On reading I find reasons to justify it; grapes and physical space transmit mineral and fruity aromas and flavours like no other, the former coming from the slate soil, the latter from the golden skin of the grapes, whose waxy prune is charged with richness by the double lateral sun from the west and the reflection in the river.

Reinhard Löwenstein considers himself a modest winegrower, but he has a mystical sense of his work. This mysticism goes back four hundred million years to the Devonian period, when the shales of his land were formed. And the sense of taste was also formed, which mankind, he tells us, inherited from the fish, since it was also in that period when the fish came out of the sea to settle on land as reptiles, guided precisely by the mouth to adapt to the new environment.

In a more recent chronology, some three hundred years ago, the mystical sense links with the ancestors. Twelve previous generations contemplate it, all of whom built the terraces and terraces inserted in the almost vertical wall that ascends from the river, some one hundred and fifty metres of unevenness, which obliges the use of ropes and rails to make cultivation possible, and to look for alternatives for tourists who do not dare to go down where they have dared to go up without looking back.

That is why wine is civilisation, to make wine is to be part of a cycle, of a chain that is longer than your own life. To drink wine is to feel our own being, because when we drink, what we drink is already part of our body. Do not look for perfection, which is always false because it is artificial, but for the harmony of humanity, which in itself is imperfect.

I promise myself that as soon as I can I must visit his cellar, where Neruda’s poem “Ode to Wine” is written on glass walls, a tribute to culture and wine as the taming of something wild. I had no intention of reading it – nor could I, since it is in German – but only of appreciating the spirit of the winemaker and the taste of the calligraphy. I wonder what it would sound like in Teutonic:

“… Wine

stirs the spring,

joy grows like a plant,

walls fall,

rocks fall,

chasms close,

singing is born…”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!