The book that serves today as a pretext for these letters, which are always intended to be about wine, is EL BOUQUET DEL MIEDO (The Bouquet of Fear). Its author: XABIER GUTIÉRREZ. Published by Planeta in 2016, 2017, in its ‘Crime and Mystery’ collection.

It is ‘The second case of Deputy Commissioner Vicente Parra’, who belongs to the Ertzaintza (Basque police force) and is recognised in the typological category of fictional detectives for his attendance at wine tasting courses.

With this background, he is confronted with the murder of a female winemaker, ritually carried out with a ‘corquete’. According to Cesáreo Goicoechea’s Vocabulario Riojano (Rioja Lexicon), the ‘corquete’ is “the tool used by the grape pickers to cut the bunches of grapes”, to which is added, to show off occasional culture, the rhyming saying: ‘Marcos Marquete, vendimiador sin corquete’ (Marcos Marquete, grape harvester without grape hook); which means that “when it freezes for San Marcos – on 25 April – the grape harvest is lost”.

The plot takes place between San Sebastián (particularly the Antiguo district) and Laguardia in Álava. It is a to and fro along the road that joins them, of which the local road that begins when you leave the annoyingly busy highway Nacional I at Briñas and runs through the Sonsierra of La Rioja to the capital of La Rioja in Alava is of particular interest. This road zigzags in parallel, with sacred respect for the vineyards, between the river Ebro to the south and the Cantabria mountain range to the north. Its magic and beauty is such that it attracts even the most regular users, who, in their rapture, neglect the traffic with potentially fatal results.

The winery where the female winemaker used to work is located in Laguardia, and plays a leading role in the work, from the very fiction of the possible existence of such a hundred-hectare vineyard that supports the mansion, on the hillside of the mountain range that looks towards the walls of the illustrious town.

In the book we find many references to wine, its production and tasting, but, in our view, they would not add anything particularly evocative to our conversation to be dealt with here. Thus, little can be said about our subject, which is wine, and less should be said about the plot. In fact, the story could have been played out in a similar way in a hardware store, simply by exchanging the shears for a spanner. What the bouquet of the wine essentially provides is verisimilitude. It is the glamour of the cellar that explains and gives meaning to the storm of passions that is drunk inside it. Hardly the hardware or any other gadgetry would be able to generate such feelings.

Let us talk then about wineries, but only about family wineries. Legal experts, always eager to specify concepts from which to draw conclusions that can be manipulated, describe a family business as one that belongs entirely to a single family, which manages it directly and with the intention that in the future it will continue to belong to the same family. In practice, this family business seems to sell as an example of intimate and dedicated good practice (I have just read that the Bank of Santander belongs to the so-called Instituto de la Empresa Familiar, that is, Family Business Institute). That is why not a few wineries are joining the bandwagon, even though many people, and therefore ‘their families’, are part of it, and certainly not all of them hold the power of management or can even aspire to hold it. However, without the smell of power there is no scent of family in the winery.

It is commonplace to say that, despite the deluded dreams of the founders, the family wineries, and in general any business with such a surname, remain in the family for a maximum of two generations. The first one promotes it and the second one expands it (this is an assumption). The third liquidates and exploits it. However, this statement is contradicted by statistics which show that only 30% of family businesses are passed on to the second generation, and only 15% benefit the third generation, which receives the fruits of the liquidation. No statistics can be found on the percentage that overcomes the monetary temptation of the last generation.

This is the best-case scenario. Any collective enterprise runs the risk of disagreements among the partners. This risk is inevitably more pronounced when you add the weight of family history, with its grievances, misunderstandings, jealousies and unresolved wounds. Not to mention when politicians, so concerned only with their own private gain, are added to the fray. Moreover, the founders, who are also parents, tend not to help, with wrong decisions and preferences, even aspiring to reign after death, leaving everything “tied up and well tied up”, as was said in that famous will the validity of which lasted only a few months.

There are, once again, lawyers and their concepts, what are known as “family protocols”, whereby the family establishes rules to regulate how changes can take place in the family structure (transmission by the partners of their position either among the living or inheritance by death), how quotas of power are distributed among the different members, or how the publicity of conflicts is covered by the confidentiality of arbitration. But when the ‘blood’ starts to ferment, irrationality overflows and there is no protocol that can channel it. “Knives out”.

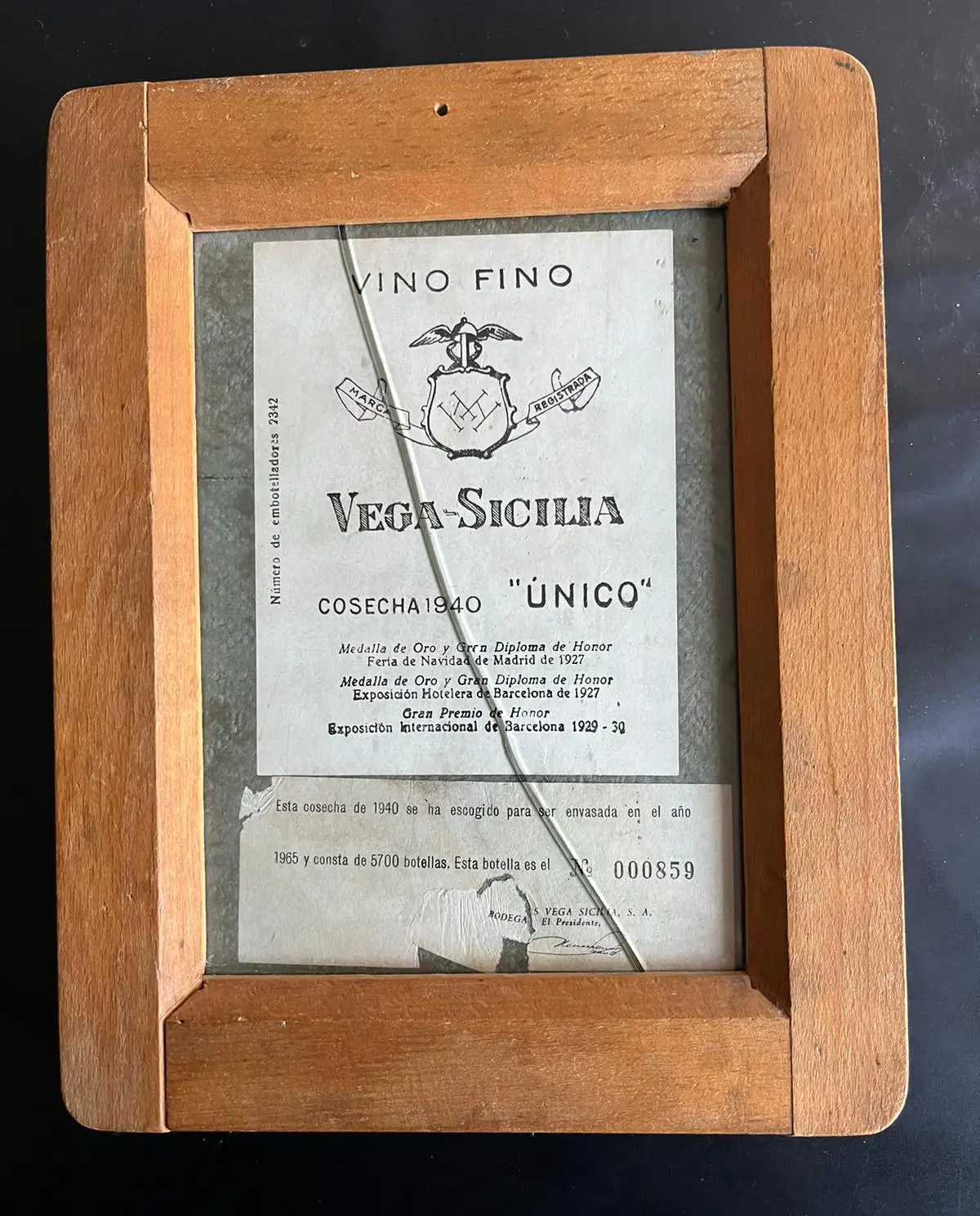

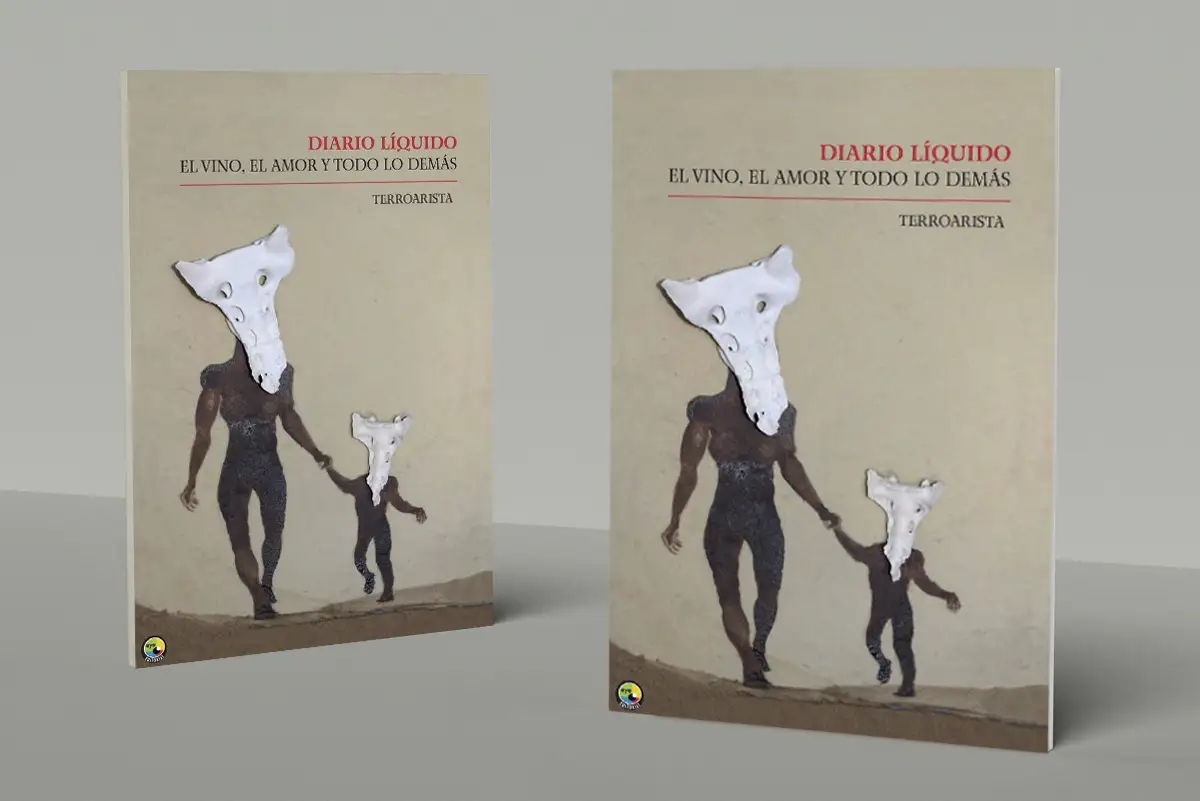

Our family winery was founded in 2022, under the name of Laventura, because “quién no se aventura no ha ventura” [1] . From the beginning we did well to take note of this, which is no guarantee of success. A few years later we changed the name to “MacRobert & Canals S.L.”, because we thought it was more honest to present ourselves with our surnames, as atypical in Rioja as our way of making wine. The third generation, the one that unites these surnames and to which our efforts are dedicated, already exists and is already helping us in our endeavours.

[1] This old Spanish saying rhymes, very much the same way it would do in English if we said whoever does not venture will have no adventure. But the real meaning of the saying is: Whoever does not venture will never be fortunate, although the rhyme is lost in translation!