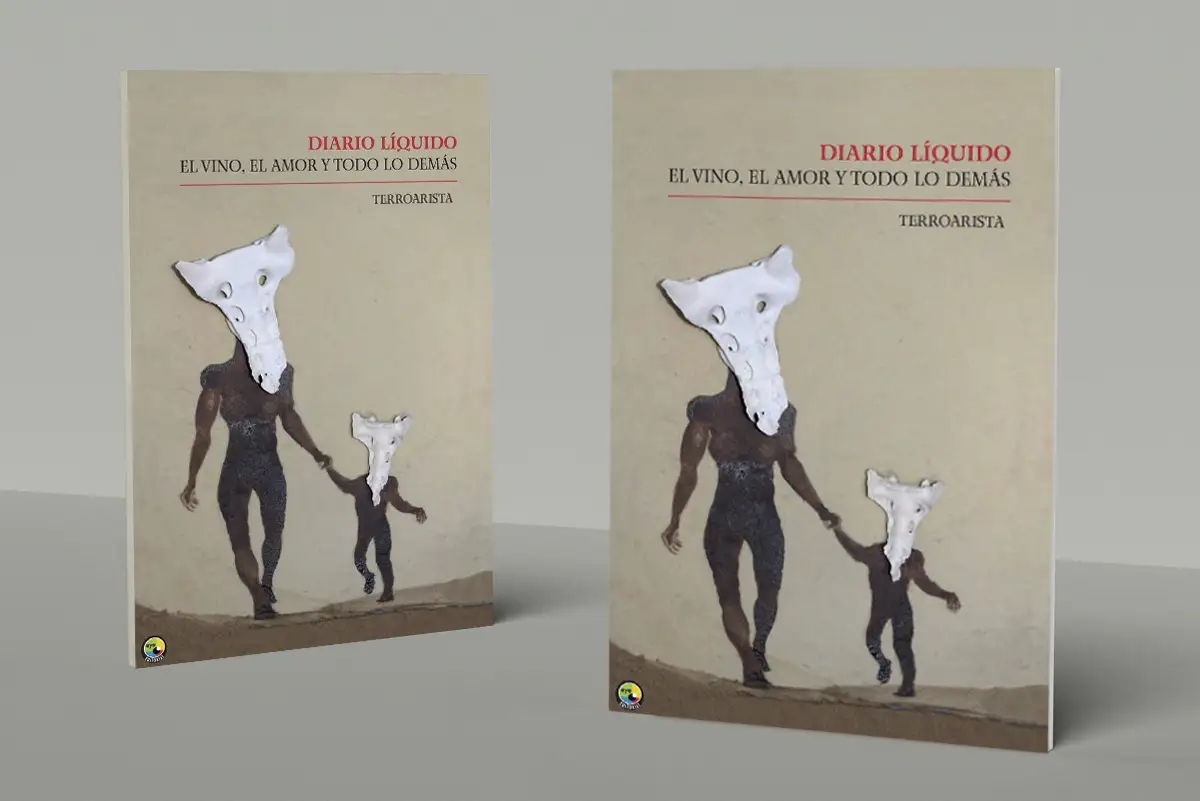

LIQUID DIARY. Wine, Love and everything else by Terroirist

Our instalment today is a book published in 2018 (2nd edition, EYE Editorial) entitled DIARIO LÍQUIDO. EL VINO, EL AMOR Y TODO LO DEMÁS (Liquid Diary. Wine, Love and everything else), and it is signed by TERROARISTA (Terroirist). The book cover immediately explains that Terroirist is a blog and that the name means “defender of the land”.

Terroarista’s blog is followed by a large number of wine lovers: www.terroarista.com . It speaks for itself. Here we should recommend it most especially, as this particular book does not seem easy to find these days.

The blog is headed by a decalogue, the starting point of which is: TERROIRIST: A person who: 1. Accepts the expression of terroir as the highest quality mark of a wine. The atypical nature of MacRobert and Canals’ wine within the land of Rioja is also justified by means of a decalogue, the final point of which reads: Because we are not terroirists or marketeers, we are humanists; in wine, a large part depends on the attitude of the person who makes it and the instruments he or she uses.

There is no contradiction. Without the hand of man there is no wine on earth. The careless assertion that that hand always harms nature is a form of denialism, even if it is vaccine denialism. God save us from all fundamentalism, including that of its followers. And from self-serving polarisation. Either the bias: you are natural versus you are commercial, or its opposite, that is, the defect is intrinsic to natural wine. Wine is always an artifice. Its balance and goodness are in the man who loves nature and defends it.

Let us talk about the book, although I have already said that we must follow the blogger. Its review is a must, as is that of any book read with the aim of improving our knowledge of wine, or the stories to tell about it; at least as an anticipated form of redemption in case we claim to be our own any reflection or consideration we may have read, without remembering who it was who contributed to make it ours.

The book tells the story of a pilgrimage that Terroarista undertakes through Italy with a friend, An, also anonymous; she on foot, he on a bicycle. It takes place along part of the so-called Via Francigena. The Italian part runs from Gran San Bernardo (warning!, closed in winter) at the top of the Dolomites to Siena in the heart of Tuscany (it has a coda without a pilgrimage in the film Roma Città Aperta).

The Via Francigena guides pilgrims on their way from Canterbury Cathedral to St Peter’s Cathedral. As with all pilgrimages, however, the departure point must be the one closest to home. Its initial route of 1,760 kilometres was established in the year 990 by Sigerico -archbishop of the first mentioned cathedral known as “the Serious”, not to be confused with our Visigoth king-, eventually taking the name of Via Francigena, by which it is known today. However, our guide limits his route to the Italian part that, as we have already said, goes from the Gran San Bernardo to Siena. The pretence that drives them is not ecumenical, but the no less religious one, with the aid of monks, of demonstrating that all pilgrimage routes are wine routes. And it certainly gives good proof of it. The official website is: https://www.viefrancigene.org. You can also check the website of the Association in Spain at: https://francigenavia.wordpress.com.

Today the pilgrimage unites two Christian faiths that have not been at peace with each other throughout history, so it can have a much greater religious meaning. However, it is not this that encourages our protagonist, who confesses that he undertakes the journey with the aim of demonstrating that all pilgrimage routes are in fact wine routes. It was monks, however, who proved him right. This is corroborated by successive libations of which he gives a good account, although little by little the journey becomes an epiphany, a revelation that implies a vital change. As Paco Berciano says in the prologue, the “road movie” gradually changes into a “wine movie”; then the road and the wine fade away and the story remains.

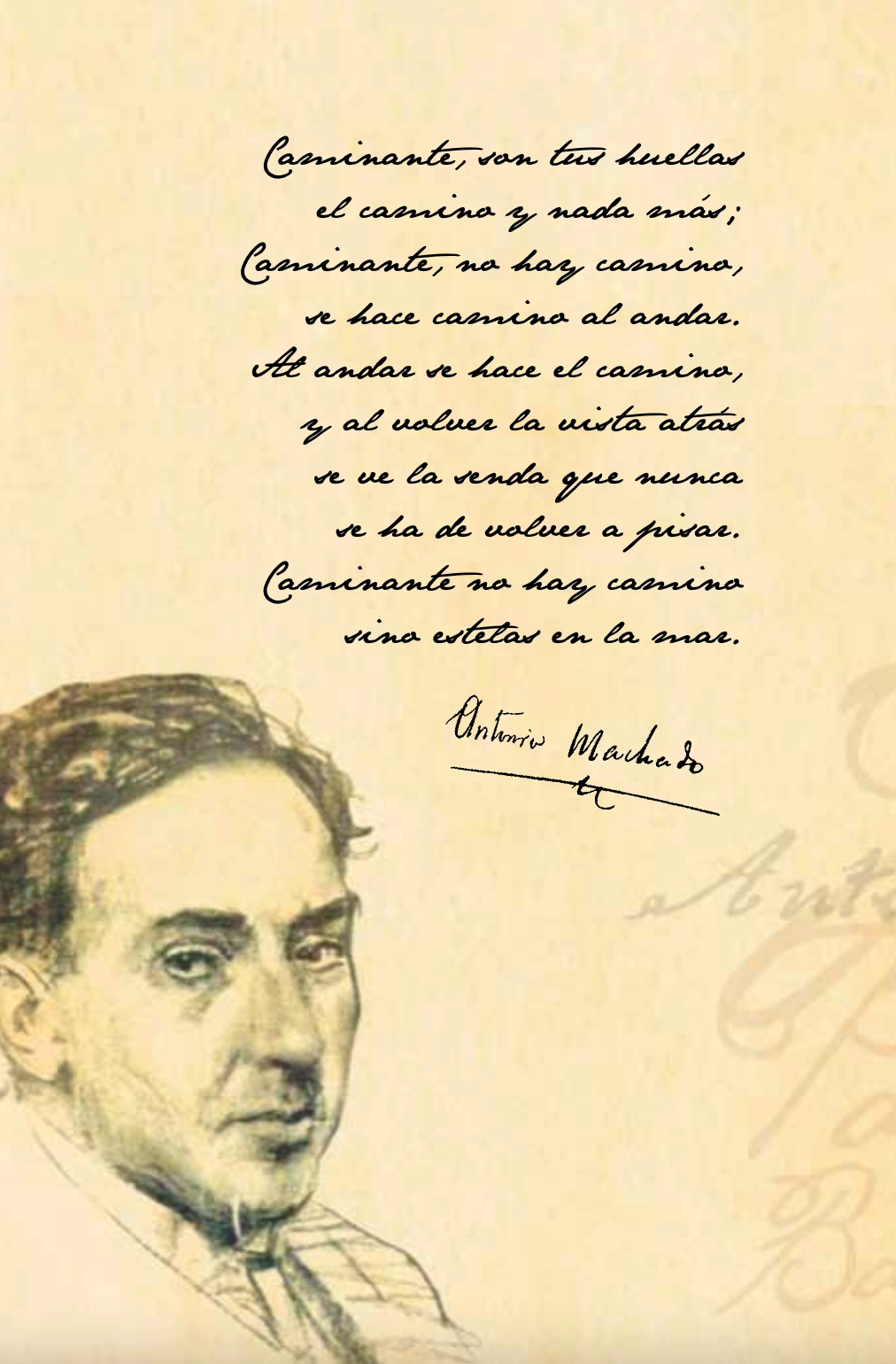

All the paths that are trodden are initiatory. Some of them go even further and are true epiphanies. The one to Bethlehem undertaken by the three Magi, or wise men, is the one that gives the saga its title. It is followed shortly afterwards by the one to Damascus, where Saul saw the light that made him fall off his horse, and off his principles. Later, that of Santiago de Compostela, and also any of the “romeros” (pilgrims) that lead to Rome, according to the poem written by A. Machado.

“Pilgrim, to go to Rome,

what matters is to walk;

to Rome from everywhere,

from everywhere you go”.

As in the case of the Via Francigena, there are also other more interior paths: Machado’s path that is made by walking, Teresa of Avila’s path of perfection, or the quixotic path that undoes wrongs.

However, in no case are epiphanies exportable. They only manifest themselves in the one who experiences them. However careful, precise and heartfelt its telling may be, it will never effect any change in the reader, no matter how moved he may become. So let us leave the story of the terroirist in its privacy, for the one who confessedly wrote it, and let us entertain ourselves with what it brings us physically about the journey itself, especially about the wines that have summoned us here.

As for the general physical circumstances, it is fortunate that the sufferings of the pilgrims, whether on foot or on a bicycle, cannot be transferred, so we will not go into them either, although here, indeed, the experience of others can serve as a guide. What really is of interest to us is the description of what is seen and what is drunk. We remain thirsty for both. This frustration, however, hides a grudging praise.

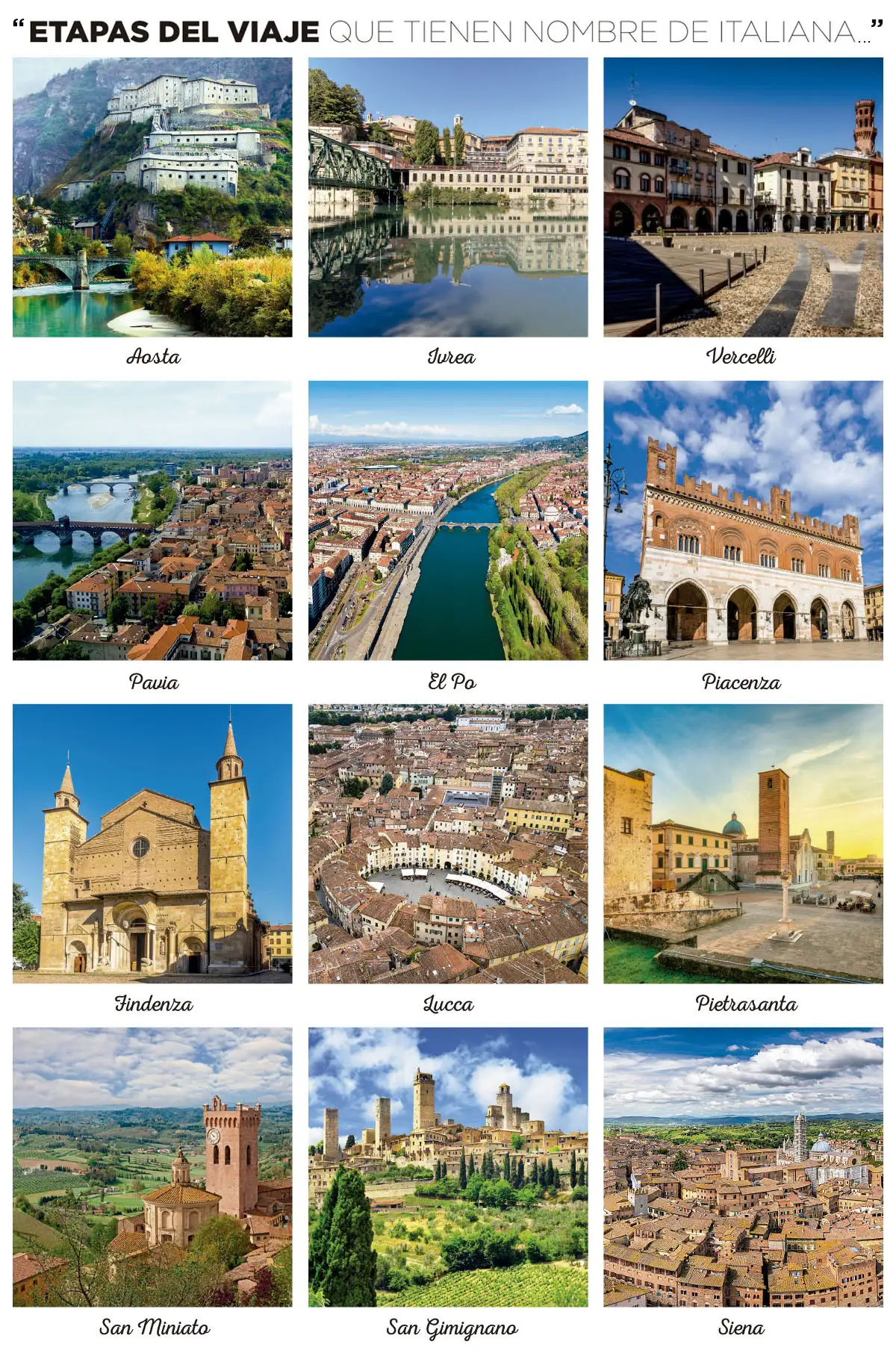

He tells us many things about what he sees – roads, paths, trails, towns, villages, mountains, landscapes, monuments, hostels… -. Stages of the journey with names of Italian, or rather mythical, beauty: Aosta, Ivrea, Vercelli, Pavia, the Po, Piacenza, Findenza, Lucca, Pietrasanta, San Miniato, San Gimignano, Siena…

Regions that add to the mythical character of their wines: Piemonte, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany… On these, the ones he finds, or could find, he expands. If he leaves us thirsty, it is because he also entrusts us with the search, the discovery. We already know the path from when we talked about pairing: trial and error. The risk is always rewarded, even if it is not always rewarded by the wine. We must reject the comfort of habit and the impoverishing advice of the algorithm.

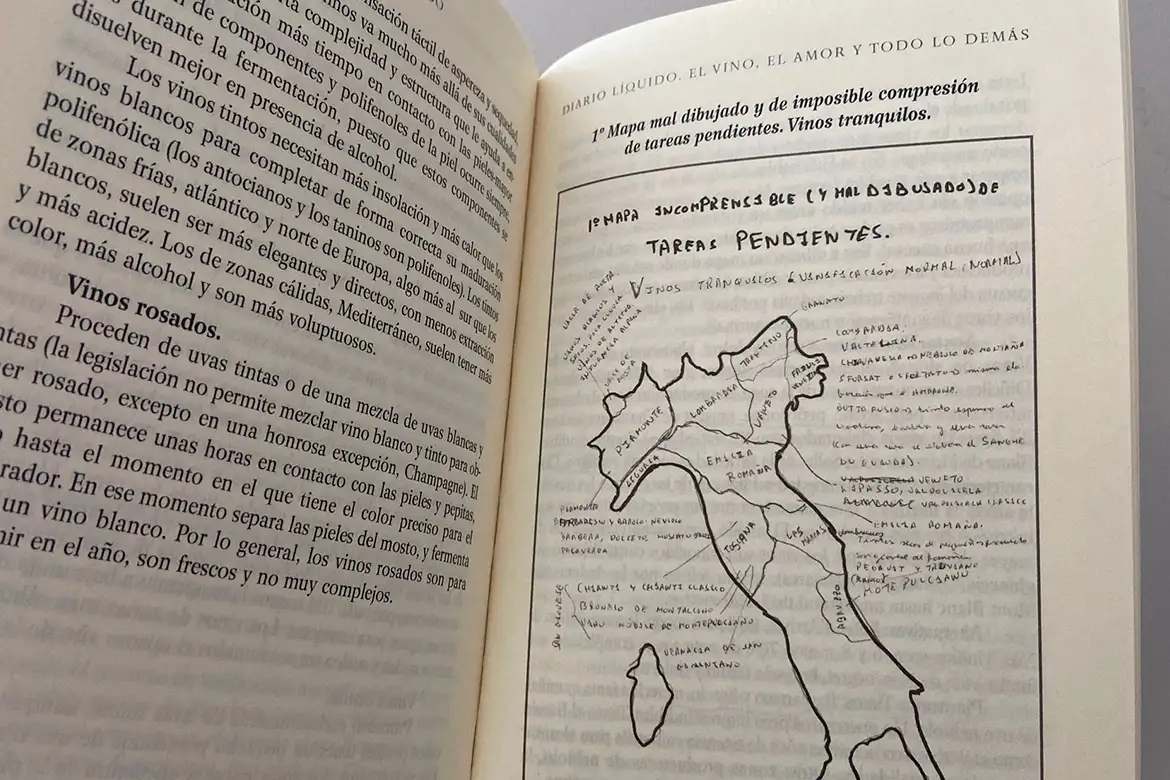

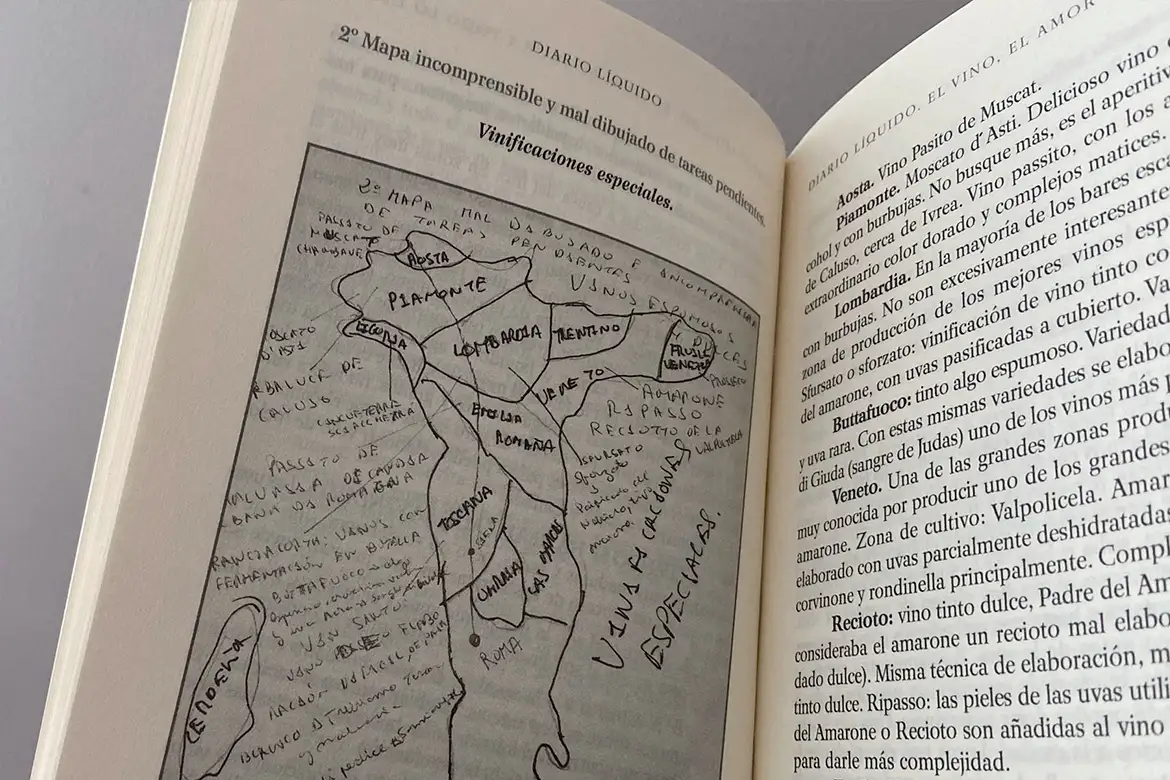

Intercaladas entre las distintas etapas del trayecto se encuentran consideraciones escolásticas sobre la materia. Esparcidas aquí y allá entre las 381 páginas que componen el libro encontramos una treintena de interrupciones en el viaje para darnos un repaso enológico. Las lecciones duran menos de media docena de páginas, sin ninguna pretensión de ser magistrales, sino la de ayudarnos a formar nuestro propio criterio. Independiente, vale decir honesto. Las materias abarcan casi todo el temario: historia, miedos versus reglas, elección y pistas, denominaciones y su complejidad, variedades vitícolas, añadas, bodegas y hacedores, temperatura, gurús y otros animales (homenaje a Durrel, el naturalista), prescriptores y consejos, elaboración y vinificaciones general y especiales, la edad, las barricas, el cuidado de la tierra…

I particularly remember some of the lectures. For example, the one in which he places (in terms of merits and demerits) both Robert Parker and Alice Ferney in their proper place (the latter does not mince her words in proclaiming that she has saved the world from the former). Or the one in which he rejects the wines already abducted by the system, whether or not they are defined as natural, (down with single thinking! “Some wines are able to generate emotions, to excite you, to make you feel. If the emotion is surprising and profound, it is engraved in your memory and makes you happy. It does not matter the origin, or the ageing, or where the fermentation took place, or the colour, or the price…”). Or the one devoted to the fathers of biodynamics, Steiner and Joly: it is the love shown for the vineyard, regardless of esoteric practices of faith, that will be measurable in the results.

The Francigena project can undoubtedly be a good project, in terms of life and wine.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!