WINE AND LETTERS (I): Taste by Roald Dahl

There is some unanimity on the Internet that Roald Dahl published Taste in The New Yorker magazine on 8 December, 1951. I have also found some pages that tell us that it had previously been published in the Ladies Home Journal in 1945. The year is always very important when talking about wines, so this first publication is suspicious since one of the wines mentioned (or tasted) in the book is precisely from the 1945 vintage; perhaps the author was updating the vintage according to the date of publication. The clarification remains for anyone who likes doing research.

Download the full text of the original story here: Taste by Roald Dahl.

If you are more of a listener, I recommend Aaron Lockman’s dramatization: Aaron Reads: Taste by Roald Dahl – YouTube

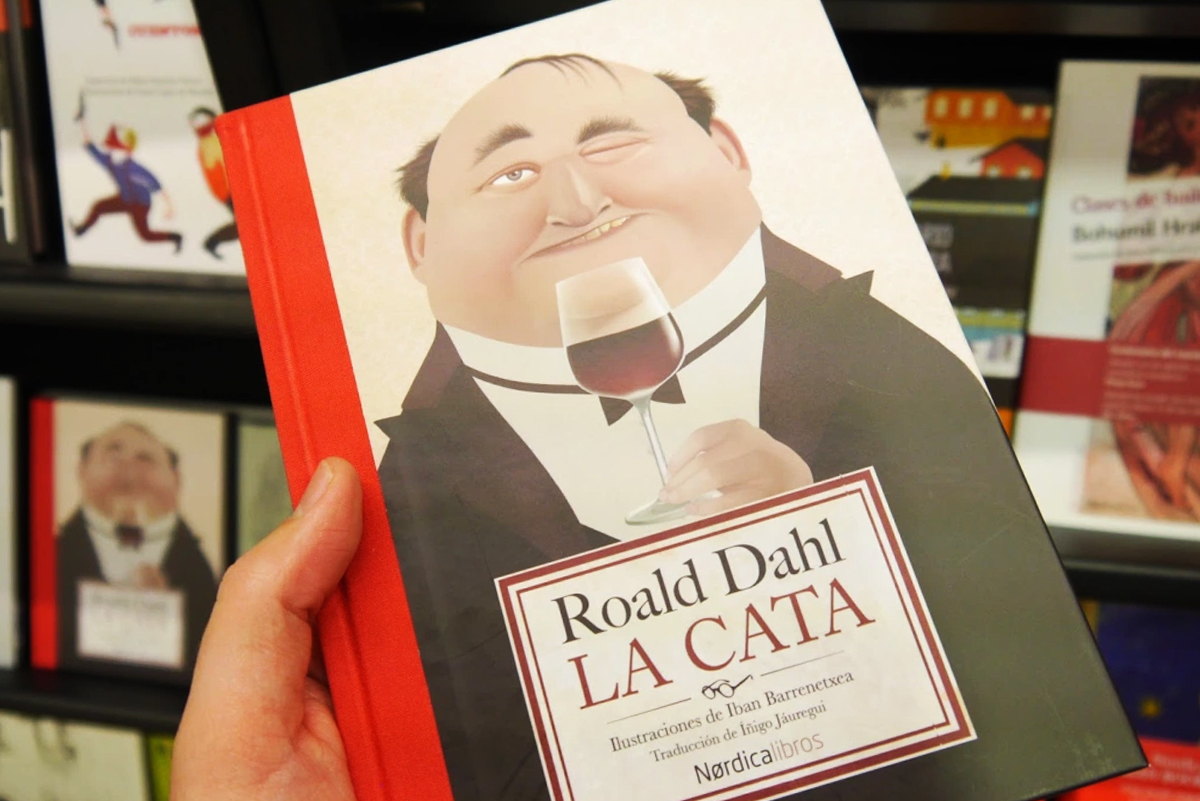

There is a Spanish translation: “La Cata”, by Iñigo Jáuregui, carefully edited by Nórdica Libros SL, with magnificent illustrations by Iban Barrenetxea in 2014, which is now in its tenth reprint.

You can also find on the web many other stories by the author, whose sense of humour is proverbial. Some of them are related to eating and drinking, which is what interests us most here; among the children’s stories, I can suggest the one about the Anteater, literally fed, this type of bear, by the peculiar English pronunciation, and among those for adults, Lamb to the Slaughter, which shows us the extra gastronomic usefulness of his leg.

Let me say no more about them, because I don’t want to spoil the stories for you. With this one –Taste– it is truly difficult to do so, because I am burning with the desire to tell you why I consider it a masterpiece. My intention is probably futile because as soon as you open any webpage about it, they will spoil it for you. I want to avoid that, and therefore I will limit myself strictly to the aspects that concern us here, which are those related to wine. I will divide them into four sections: (01) the wine taster and the wine supplier, (02) the act of tasting, (03) the language of tasting, and (04) the wines tasted

(01) THE CHARACTERS:

Here you have the members of the table, according to Iban Barrenetxea’s apt image. We will refer exclusively to the main characters that you can easily identify.

The proponent of the tasting, that is to say, the host, is

- a stockbroker. To be precise, he was a jobber in the stock market, and like a number of his kind, he seemed to be somewhat embarrassed, almost ashamed to find that he had made so much money with so slight a talent. In his heart he knew that he was not really much more than a bookmaker – an unctuous, infinitely respectable, secretly unscrupulous bookmaker – and he knew that his friends knew it, too.

So, he was seeking now to become a man of culture,

- to cultivate a literary and aesthetic taste, to collect paintings, music, books, and all the rest of it.

Knowing about wine was part of it, and he seemed willing to do anything to be recognised for his ability to choose good wines.

The taster is a famous gourmet; he is defined almost as a true professional,

- He was president of a small society known as the Epicures, and each month he circulated privately to its members a pamphlet on food and wines. He organised dinners where sumptuous dishes and rare wines were served.

A geek, as we defined him in the first of these letters? Perhaps… Would we today consider a geek someone who describes the custom “to smoke at table” as “a disgusting habit”? Surely not; and who refuses to smoke “for fear of harming his palate”?

In any case, a true wine tasting professional. At that moment he becomes

- Somehow, it was all mouth – mouth and lips – the full, wet lips of the professional gourmet, the lower lip hanging downward in the centre, a pendulous, permanently open taster’s lip, shaped open to receive the rim of a glass or a morsel of food. Like a keyhole, I thought, watching it, his mouth is like a large wet keyhole.

In short, two oenological archetypes: the connoisseur, who cannot bear to be told that he does not know everything, and the upstart, who cannot bear to be told that he knows nothing.

(02) THE TASTING:

The host first pours a thimbleful of wine into his glass, literally “tipped” it, as the wine rests in a wicker basket with the label facing downwards – the typical “ridiculous” basket – and then fills the glasses of the others. Filling here means “filling up”, i.e., what I understand to be up to the top, maybe not to the rim of the glass, but it looks like the typical filling up of a money-making restaurant that tries to make you drink wine (taking out even the second bottle, as soon as they see that the level of consumption has dropped). Such an overflowing glass, so pretentious and vain in its senseless measure, prevents the wine from tasting and smelling until it reaches its rational measure. Perhaps an insinuation in this case, like so many others scattered throughout the text, about the host’s lack of knowledge and surplus wealth.

In any case, the glass was not so full that it prevented the taster’s nose from entering, the act with which he begins his “impressive performance” – and it was indeed quite a “performance”!

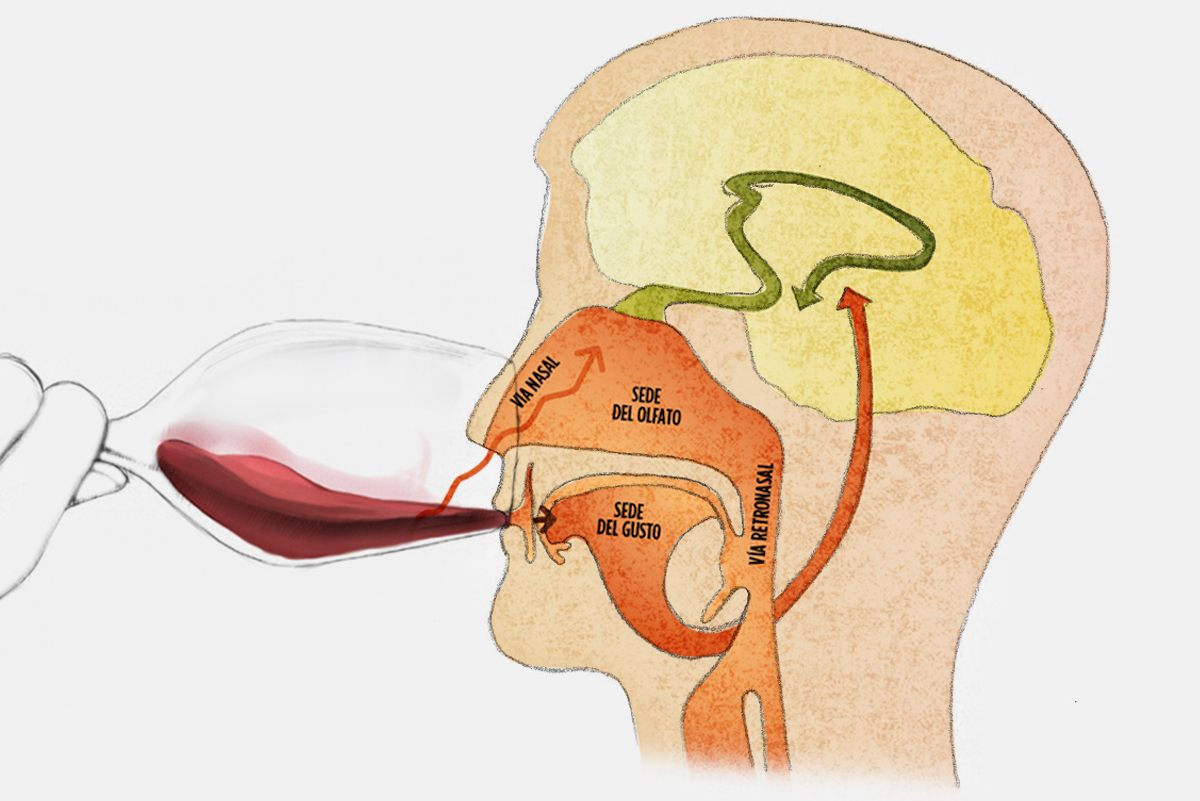

- The point of the nose entered the glass and moved over the surface of the wine, delicately sniffing. He swirled the wine gently around in the glass to receive the bouquet. His concentration was intense. He had closed his eyes, and now the whole top half of his body, the head and neck and chest, seemed to become a kind of huge sensitive smelling-machine, receiving, filtering, analysing the message from the sniffing nose.

For at least a minute, the smelling process continued, then, without opening his eyes or moving his head, Pratt lowered the glass to his mouth and tipped in almost half the contents.

He paused, his mouth full of wine, getting the first taste, then, he permitted some of it to trickle down his throat and I saw his Adam’s apple move as it passed by. But most of it he retained in his mouth. And now, without swallowing again, he drew in through his lips a thin breath of air which mingled with the fumes of the wine in the mouth and passed on down into his lungs. He held the breath, blew it out through his nose, and finally began to roll the wine around under the tongue, and chewed it, actually chewed it with his teeth as though it were bread.

After a little sip and a lot of talk, as we shall see below, he continued with his “performance”.

- Again he paused, took up his glass, and held the rim against that sagging, pendulous lower lip of his. Then I saw the tongue shoot out, pink and narrow, the tip of it dipping into the wine, withdrawing swiftly again – a repulsive sight. When he lowered the glass, his eyes remained closed, the face concentrated, only the lips moving, sliding over each other like two pieces of wet, spongy rubber.

And the little sips continued until the end of his memorable performance.

(03) THE LANGUAGE OF WINE TASTING:

The descriptive language of wine would surely need many instalments of this series of wine and letters. Today it is a highly standardised language, at least very recognisable among experts or professionals in the sector. The eighties of the last century are often referred to as the time when this need to establish parameters of understanding was felt, even if these were abundant in metaphors and plastic images.

Roald Dahl, if we think about the date of publication of this short story, turns out to be a pioneer in the matter and points out the reasons for this need that was later felt to understand one another. Already at the beginning of the story, when describing the taster, he tells us that

- he had a curious, rather droll habit of referring to it as though it were a living being.

- ‘A prudent wine,’ he would say, ‘rather diffident and evasive, but quite prudent.’ Or, ‘A good-humoured wine, benevolent and cheerful – slightly obscene, perhaps, but none the less good-humoured.’

And at the start of the tasting itself:

. ‘Um – yes. A very interesting little wine – gentle and gracious, almost feminine in the after-taste.’

establishing a gender parameter that was then repeatedly used until, like everything else, it was revised. We will have to come back to this on another occasion.

(04) LOS VINOS:

Three wines were scheduled to be tasted, at least three wineglasses per person rested on the dinner table, ready for a feast. However, one, the last one, was not tasted. A sweet wine? A port with the dessert? A surprise with the cheese? We know that there was a lot of shiny silver, but not the nature and distribution of the cutlery, so there is no clue as to the destination of that third glass, of wine of course, as that is what it is called. A real shame, known as it is by its own admission the extent of Roald Dahl’s cellar. It would have been appropriate and interesting to know his taste for that final moment, for I am convinced that he was depicting his own tasting in the story. For particular reasons I exclude champagne altogether.

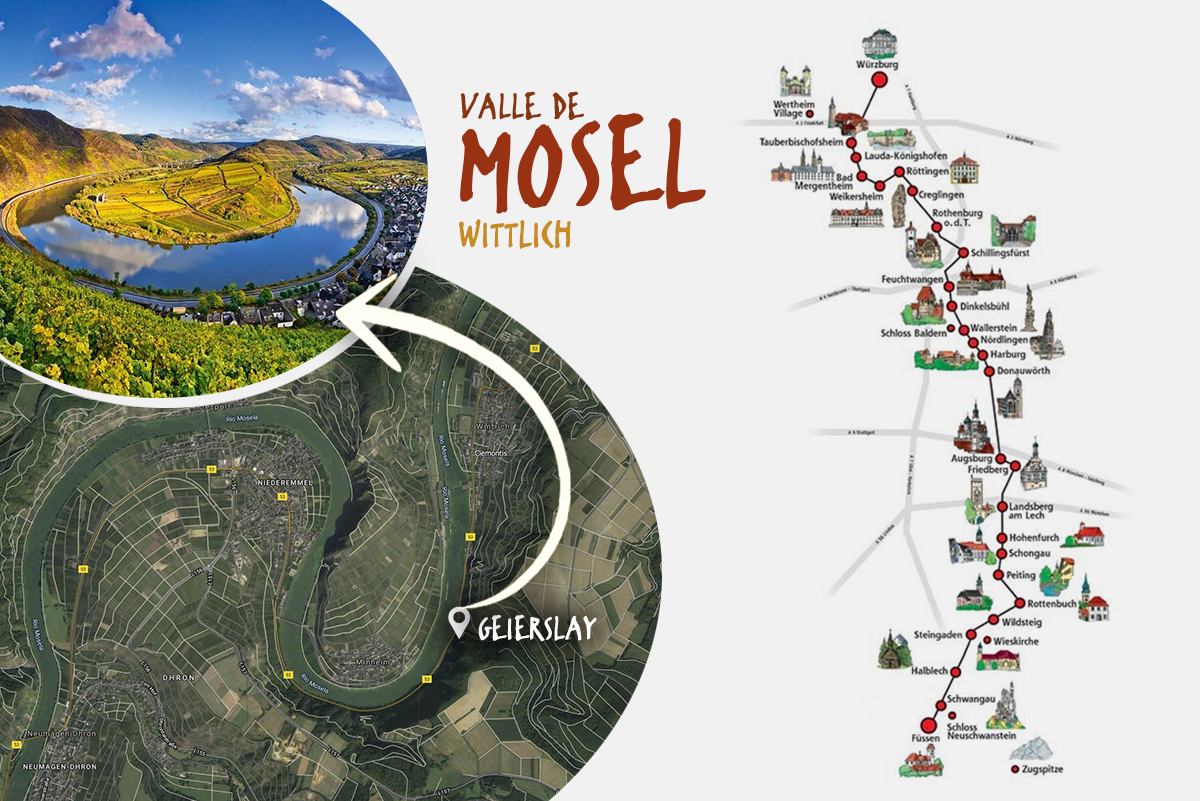

Of the two wines we have left, one is not really the subject of a tasting. It is drunk, even swallowed without compassion, but not tasted or analysed. And it was certainly not worthy of such mistreatment; it was a Mosel, a Geierslay Ohligsberg, 1945, the product of a purchase that the host had made the previous summer in the same small village of Geierslay, almost unknown outside Germany. He also explains that his choice was not only for that reason, but because it would have been barbaric to serve a Rhine wine before a “delicate claret”, which is what a lot of people “who don’t know any better” would have served:

- A Rhine wine will kill a delicate claret, you know that?

So, a Riesling, almost certainly from that area of the river called Middle Moselle, a vineyard planted on the extreme slope down to the water itself, facing west to receive every last drop of an elusive sun, and with a dark, heat-absorbing slate soil, dry and immediate drainage. A personal weakness!

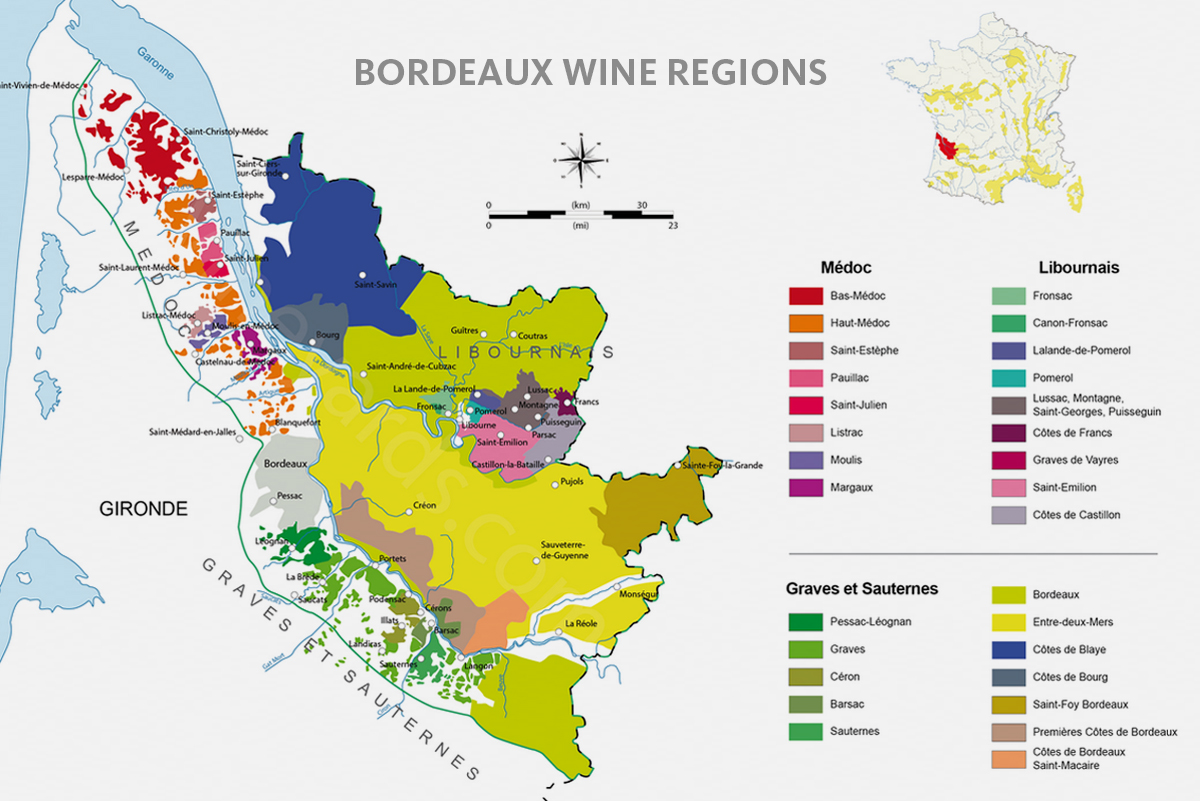

This brings us to the “claret”, which we are told from the outset is the wine to be tasted. The image that this word literally conveys is not very accurate. The “claret” is a typical expression to refer to a Bordeaux -although later by extension it was applied to wine from other areas, such as Burgundy, and even Rioja itself-. This is the wine produced in the Aquitaine region. Such a reference was coined centuries ago, perhaps from the same time that the duchess Eleanor gave it to her “English” husband Henry II, the first Plantagenet – in addition to giving him five children that she had denied to her first husband, King Louis VII of France, who had repudiated her for it. Indeed, even today the English still very much include Bordeaux wine as part of their empire, and of their eccentric idiosyncrasies.

From the beginning of the story, it is clear and obvious that the wine to be tasted could not be any other.

The host explains the purpose of the tasting beforehand; it is a matter of locating the hidden origin of the wine, its producer, the “terroir” in short. Insofar as it is not one of the famous great wines, such as Lafite or Latour, he understands that the expert could at best locate the district it comes from, i.e., whether it is St Emilion, Pomerol, Graves or Médoc, but each region has several communes, and these in turn have many, many small vineyards; it is impossible for a man to differentiate between them just by the taste and smell of the wine. And he does not mind adding that the wine comes from a small vineyard surrounded by other small vineyards.

With such a background, our taster prepares himself for the tasting, body and soul as we have seen.

He eliminates the regions of Saint Emilion or Graves, as the wine is “far too light in the body” to belong to one of them.

It is obviously a Médoc.

Once here, he excludes Margaux – it lacks the “violent bouquet” that Margaux has -, and he excludes Pauillac – because unlike the wines of Pauillac, “it is too tender, too gentle and wistful”. And here the personality of the wine taster speaks at length: The wine of Pauillac has a character that is almost imperious in its taste, And also, to me, a Pauillac contains just a little pith, a curious dusty, pithy flavour that the grape acquires from the soil of the district. No, no. This – this is a very gentle wine, demure and bashful in the first taste, emerging shyly but quite graciously in the second. A little arch, perhaps, in the second taste, and a little naughty also, teasing the tongue with a trace, just a trace of tannin. Then, in the after-taste, delightful consoling and feminine, with a certain blithely generous quality that one associates only with the wines of the commune of St Julien.

This is a Saint Julien, so there is no room for error. Once here, it is necessary to fix, let’s say, the category. It is not a first growth, it is not a second growth, it is not one of ‘the greats’. It lacks the quality, the strength, the radiance. Maybe a third growth, but no, it is definitely a fourth, even if it is from a great year.

Within the “quatrième cru” of Saint Julien, the tannin in the middle taste, and the quick astringent squeeze upon the tongue, takes us to the small vineyards of the Beichevelle area. But not Beichevelle itself, somewhere nearby, perhaps Château Talbot? No; a Talbot comes forward to you a little quicker than this one, besides if it is the ’34 vintage, as he thinks, it could not be. A vineyard close to both, almost in the middle. And it can be none other than the small Château Branaire-Ducru, and the 1934 vintage. Charming little vineyard, lovely old château, so well-known that he cannot conceive why he did not recognise it at once.

It is not appropriate to reveal whether the wine has been guessed correctly or not. Our intention, as we said, was limited to pointing out some characteristics of wines that I hope will be of interest to you and to invite you to participate in a story that, as the classic saying goes, both instructs and delights.

We come to an end, but not without completing the oenological references, as the Moselle is served with fried whitebait in butter – how can we not long for the similar ‘chanquetes’ from the Bay of Cadiz, but fried in olive oil and washed down with a manzanilla sherry from el Puerto? -, and the Bordeaux would naturally be served with a piece of roast beef and a vegetable garnish.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!