On the trail of vineyards (V): Sara Pérez and Pierre Overnoy

SARA PÉREZ. La Universal. Partida Bellvisos Mas Martinet. Priorat-Montsant. Tarragona. Tarragona. Spain. The Venus of the vineyards.

We return to the Priorat, this time by the hand of a lady. The Priorat has a harsh and extreme beauty. “The Priorat,” she (Sara) tells us, “is like a circus of small hills and, orographically speaking, it is very dramatic. It has many slopes and, depending on where you are, the panoramic view is very different if you look up, down or both sides”.

We learn in the book that it was Sara Pérez’s drive, independence and vitality that led to the regeneration of the region’s wine, and therefore that of the whole region, from the 1990s onwards. They were supported, of course, by the efforts that the previous generation, her father Josep Lluis and a few others, had made a decade earlier.

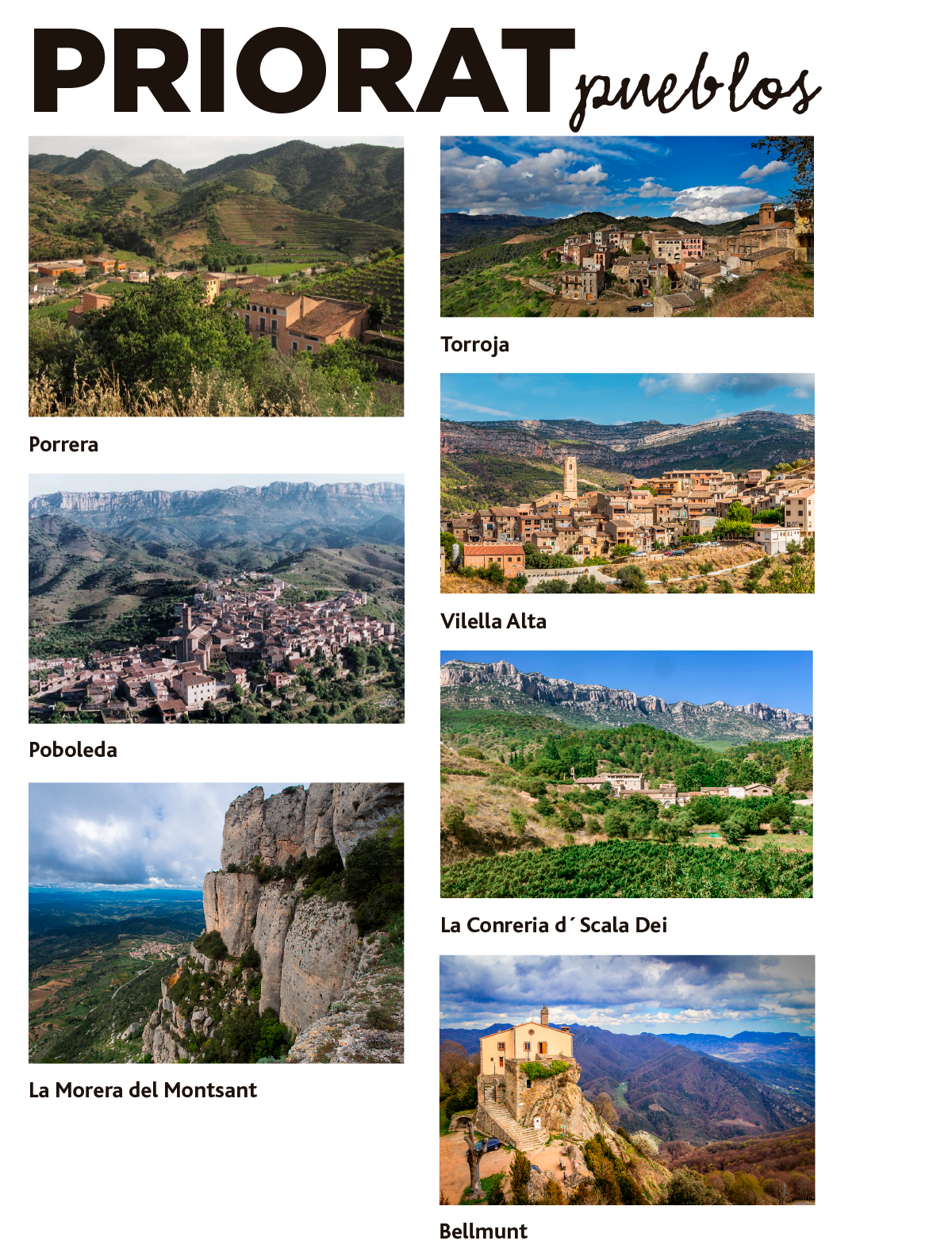

Porrera, with its Cims de Porrera, was the starting point. Other villages followed: Torroja, Poboleda, Gratallops, Vilella Alta, Vilella Baixa, La Morera del Montsant, La Conreria d’Scala Dei, El Lloar, Bellmunt… Names that have in me the special resonance of what I experienced there (which was described in a previous letter).

I must mention one in particular where the regeneration was also collateral, as it not only affected the wine, but also its industry. I am referring to Miravet, a village bordering the Ebro from the shallows of its banks to the top of a ravine cut to the edge that looks down on it with fascination. A village where I spent many happy days with good friends and good wines of the area and some magical nights in its Templar castle. In this village Sara achieved the regeneration of the profession of “cantarero”, and had the jars – “amphorae”- made in which to apply all her inner vital energy to the wine with “botijo” kinetics, according to which the more external heat there is the cooler the interior is preserved.

The village of Miravet on the banks of the Ebro.

We learn other things from her.

For example, in the Priorat region, Garnacha suffered from the problems of its fragility, so that it was replaced by Carignan -like in the Rioja region, where Tempranillo was introduced massively-, although there, perhaps fortunately as we can see now, the lack of resources prevented the substitution from being as massive as it has been in this region. In addition, other varieties also entered: cabernet, syrah, merlot…

Sara tells us: “I want to make wines in which the first thing you say is that it is a Priorat and then you wonder what variety it is made from. It doesn’t matter if it has syrah or garnacha. If it’s a Priorat, it’s a Priorat”. And in the Priorat, (I naturally use Spanish when I speak and write but I reproduce her words as she naturally pronounced them), she wants to “make stone wines, because this region is made of stone”. Granite and charred slate (“sablón”) sustain some of her vines. And it seems that the cold weather comes to their aid.

Again, also ecological or preservation awareness. According to Lovelock, “as long as we do not intuitively perceive the Earth as a living system and realise that we are part of it, we will not be able to react in favour of its protection and, ultimately, our own”. In it, each generation leaves a legacy that is a point of reference on which the next must reaffirm its own and leave it improved for the next generation.

And many other things that are related in the book. I felt the impulse to return to the Priorat with nostalgia and a tango grip.

PIERRE OVERNOY. Maison Overnoy-Houillon. Pupillin, Jura, France. “The discreet visionary.”

Pierre Overnoy tasting with Emmanuel Houillon.

We are in France again: Jura. As this is a lesser-known region, it is perhaps appropriate to make a preliminary location. To the east, just beyond the Burgundy area, the Jura mountains form the region, which stretches to the Swiss border. Several villages punctuate its beauty and its appellations: Salin-les Bains, Arbois, Pupillin – where we will meet our protagonist -, Château Chalon, L’Etoile… A mountainous and isolated area where the vineyards are once again tied to the human will. They occupy the lower slopes (between 250 and 500 metres above sea level).

Jura Mountains, France.

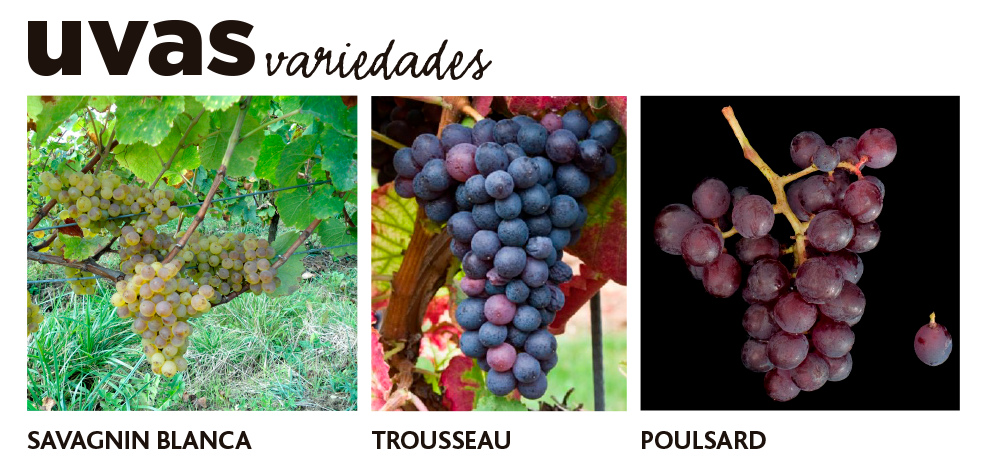

Wines can therefore not be easy, just as life was not traditionally easy. The most characteristic grapes are the red Trousseau, sullen and difficult, the Poulsard, with a paler colour and less personality, and the white Savagnin, described as cruel and fascinating. The latter is used to make a very peculiar wine, the so-called “vin jaune”, which is very similar to sherry, as it must be aged for a legal minimum of six years and three months in casks, during which time it develops a film of yeast on the surface, resulting in a bright, acidic and matured white wine. The big difference with sherry is that it always remains in the same cask and is not made using the solera system.

It is the natural and coherent space for a personality as close to nature as Pierre Overnoy to emerge.

According to his own confession, Pierre should be around 84 years old today, so it is foreseeable that the vineyards and the winery will be managed entirely by Emmanuel and his wife Anne. The book also tells the story of Emmanuel, who started working the vineyards as a teenager and ended up being made an adopted son. The spirit of the father in the wines remains guaranteed.

Emmanuel with Pierre in the vineyard.

Here we are particularly interested in the personality of Pierre Overnoy. A surname which, by the way, is the frenchification of the original Irish O’Vernoy; I am intrigued to know how the Scottish MacRobert will eventually become ‘Riojanised’.

The best way to do this is to transcribe what the authors observed about him:

“Pierre Overnoy follows an accessible philosophy that starts from simplicity as a rule, understood as respect for the life cycles of the soil and the plant, and the rule of being absolutely impeccable in the processes that take place from vinification to bottling, seeking freedom of expression in each of his wines, without added protection, authentic nudity; without heeding established codes, without waiting for the approval of the press or prescribers, searching in unexplored and at the same time ancestral paths. He seduces with his generosity, his character, with the strength of his resolve and his inspiring determination”.

Reading these lines, I could not help thinking of the infinite number of heroic “hidden lives” that perhaps only chance will make public. I was seized by images of one of them that took place in other Alpine mountains in terrible circumstances, which Pierre had also witnessed, according to what he tells us. It was precisely with that title –“A Hidden Life”- that Terence Mallick portrayed it in a film in which the most rapturous beauty contrasted with the most chilling ugliness.

Pierre Overnoy has thus become, probably unwittingly, the myth of a new category of wines: “natural wines”. This question deserves the most profound reflection, which cannot be done here, although it is worth trying to define the terms.

When we jump from people to categorisations, we start to tread on slippery ground. The creation of the category of natural wine can be used to indicate that wines that do not fit this category are no longer natural, but artificial, an adjective that carries a negative connotation. Our authors try to defend them: “Are non-natural wines artificial wines? Certainly not”.

However, in all honesty, and with the DRAE (The Dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy) in hand, the problem is not in the word, but in the prejudice. There are two definitions of “artificial” in the DRAE: 1st: “Made by the hand or art of man”. There is no doubt that this definition applies to wine, to all wine, even if it is described as natural. Previously, even Vitis viniferae itself is a human artifice created by the science that prehistoric man possessed. Wine is art, and therefore always human. 2nd: “Not natural, false”, (this is where the prejudice may lie, causing an inaccurate generalisation). All wines are artificial by humans, some people are artificial in themselves, because they do not respect the natural, and their wines will be fake.

On the other hand, it is also clear that the addition of any chemical product does not make the wine lose its “natural” category. Thus, as we read on, purists accept sulphites of around 25 mg/l and other winegrowers belonging to the movement go as high as 50 mg/l, although preferably not at the time of production. As soon as this approach is accepted for strictly sanitary reasons, doubts arise as to the non-acceptance of other products, when the reasons are strictly the same. The words attributed to Paracelsus, so often repeated here, always come to mind: “the poison is in the dose”.

Pierre himself rescues us from fundamentalist attitudes: “[Wine] is more than a drink and even more than a food. But above all it is a pleasure”.

So let us always come back to the person. As the book justifiably stresses:

“If the rise of the natural movement has served any purpose, it has been to raise awareness of the extent to which man is involved in the making of wine.”

In our Decalogue, which can be read elsewhere on this page, we said as a final point that we are not (we do not want to be) either “terroirists” or “marketeers”, but humanists. It is man – “and his circumstance”, attention must be paid to this – who is behind the vines. Today, in ecologism, in the pretence of naturalness, there can be as much marketing as in the adaptation to the fashion of consumers or prescribers.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!